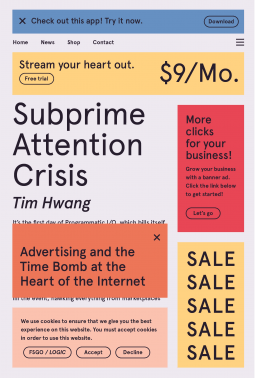

My attention span hasn’t been great lately. I snapped up some advanced copies of books about tech and society (thank you Netgalley) but it’s all too easy to let my attention slip to checking the news or, worse, to Twitter, home of the social media paradox: the platform depends on attention, while totally obliterating it. Tim Hwang’s new book, Subprime Attention Crisis: Advertising and the Time Bomb at the Heart of the Internet, out in mid-October, confirms a suspicion I’ve had for a long time. Targeted advertising doesn’t work – but because it drives so much of what we think of as “the internet” today, its approaching failure threatens to create widespread damage to our entire information infrastructure.

By pure happenstance – probably thanks to a Tweet – I also read Cory Doctorow’s new book, a free “non-fiction novella,” How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism, which makes the same point but has a different focus and offers different solutions.

Hwang’s book takes a deep dive into the inner workings of the adtech industry and compares it, convincingly and in detail, to the subprime mortgage crisis that kicked off the 2008 global economic crisis. Where the industry (dominated by Google and Facebook, with ad auctioneers busy in the background) likes us to think they are “data-driven wizards of consumer persuasion,” they are actually at the helm of a rickety structure riven by “perverse incentives, outright fraud, and a web economy on the brink.” Yeah, that sounds eerily familiar.

Hwang’s book takes a deep dive into the inner workings of the adtech industry and compares it, convincingly and in detail, to the subprime mortgage crisis that kicked off the 2008 global economic crisis. Where the industry (dominated by Google and Facebook, with ad auctioneers busy in the background) likes us to think they are “data-driven wizards of consumer persuasion,” they are actually at the helm of a rickety structure riven by “perverse incentives, outright fraud, and a web economy on the brink.” Yeah, that sounds eerily familiar.

Like the financial systems that used lightning-fast algorithmic predictions and computerized transactions to buy and sell derivatives that grew increasingly risky, the adtech industry suffers from a similar combination of hubris and opaque complexity that’s impossible to analyze clearly. Hwang draws an intriguing lesson from James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State. To administer power over a large population, you need “legibility” – a way of identifying and tabulating humans and their behavior. To do this, platforms are designed to appropriate data in order to administer ads.

Though these companies collect an incredibly vast amount of data in violation of our privacy, legibility is one-way. In spite of data about click-throughs and impressions, nobody who places an ad can tell where it will end up or whether it is actually effective. A few big corporations have an outsize impact and no incentives to improve transparency or even simple accuracy. Hwang cites a claim Facebook once made about its ability to reach a coveted American youth demographic, stating it could put ads in front of 25 million more people in that age range than actually live in the entire US; its disastrous “pivot to video” claims cost media companies time, energy, and a lot of money.

What’s more, those dollars are chasing a dwindling audience, especially among younger people who increasingly use ad blockers, and a lot of the attention metrics are fraudulent. Many ads are never seen by anyone, and a large percentage of the “viewers” for those “seen” are non-human, automated systems designed to pump up the numbers. Hwang provides an in-depth analysis of how the financial incentives parallel the subprime mortgage crisis: people have more money to spend than they have places to put it. Google and Facebook not only absorb most digital ad dollars, they are replacing the media outlets that depend on ads – newspapers, for instance. As more people get their news directly through ad-driven platforms, traditional and new media watch their ability to influence the ad industry leached away, along with attention.

Hwang names, though doesn’t spend much time on, the anti-social tendencies of ad-driven persuasion, but urges us to recognize an economic bubble that will soon burst. The longer it has to grow, the more damaging the consequences. He urges us to imagine an alternative and to do a “controlled demolition” to avoid disaster. He argues for independent industry research to inform our understanding of digital advertising’s effects, legal protection for whistle-blowers, and recommends a regulatory overhaul similar to those imposed after the 1929 crash as a model for public accountability and the rebuilding of a more robust, bubble-proof internet. Apparently it’s one that might still be largely financed by advertising, (I wasn’t sure) but it would be less fraudulent and opaque.

The internet we have, for better or worse, is yoked to the structure and prospects of the advertising economy by the business models, companies, and economics that have dominated over the last few decades. If this system of advertising is brittle, then the internet as we know it is brittle. Whether we leave these marketplaces deregulated and feral or implement systems to manage them for public benefit will define not just the future of advertising, but the future of the technologies that have shaped and continue to shape our society.

Hwang’s focus is on advertising as the financial backbone of the internet. The problems caused by giant corporations and their data-sucking assaults on privacy isn’t so much that they suck data, in his estimation, as that they suck at advertising, yet have been able to build fortunes through misleading and increasingly ineffective practices.

C ory Doctorow, too, argues that adtech doesn’t work, but his focus in more on the future of the internet and its role in human affairs than on the advertising industry. Like Hwang he looks to historical precedence and the potential for legislation as a remedy. His target, though, isn’t making the ad industry more transparent. It’s on trust busting.

ory Doctorow, too, argues that adtech doesn’t work, but his focus in more on the future of the internet and its role in human affairs than on the advertising industry. Like Hwang he looks to historical precedence and the potential for legislation as a remedy. His target, though, isn’t making the ad industry more transparent. It’s on trust busting.

Like me, he finds Shoshanna Zuboff’s magisterial tome, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, far too uncritical of capitalism and far too credulous about big tech’s claims. “She’s right that capitalism today threatens our species, and she’s right that tech poses unique challenges to our species and civilization, but she’s really wrong about how tech is different and why it threatens our species.”

Big tech claims to be able to persuade – that’s its product, and its excuse for gathering so much data about us. But it’s mostly hype. “Surveillance capitalism assumes that because advertisers buy a lot of what Big Tech is selling, Big Tech must be selling something real. But Big Tech’s massive sales could just as easily be the result of a popular delusion or something even more pernicious: monopolistic control over our communications and commerce.”

A political ad campaign can’t exert mind control, though it may help you find others who think like you and encourage you to act publicly on those thoughts. In a way this is disturbing. It would be oddly comforting to think brainwashing is at work, when actually it seems a large percentage of Americans are wholly in favor of white supremacy and authoritarianism. (Historians and Black folks keep reminding us that it’s inaccurate to say “this is not who we are.” This is who we are. We just weren’t paying attention.) Here I think there’s a useful distinction to be made between the persuasion people pay for using targeted ads and the slow, deliberate grooming that far right extremists engage in, often abetted by clever use of social media’s prioritization of sensationalism in their recommendation algorithms. Or as Doctorow puts it, there’s a difference between technological brainwashing and fraud – “in which someone’s true belief is displaced by a false one by means of sophisticated persuasion.”

The problem isn’t the secret power of algorithms to change our minds. It’s more basic than that. “Controlling the results to the world’s search queries means controlling access both to arguments and their rebuttals and, thus, control over much of the world’s beliefs. If our concern is how corporations are foreclosing on our ability to make up our own minds and determine our own futures, the impact of dominance far exceeds the impact of manipulation and should be central to our analysis and any remedies we seek.”

Doctorow discusses adtech in terms very similar to Hwang, but his underlying interest isn’t in the perils of faulty marketing, it’s in surveillance and monopoly. Facebook not only spies on us all the time, it locks in our attention and booby-traps the entire web through its Facebook and Instagram buttons that gather data about you even if you don’t have accounts. (Hint: use Privacy Badger.) It’s a one-way trap: “Though it’s easy to integrate the web with Facebook — linking to news stories and such — Facebook products are generally not available to be integrated back into the web itself.” And while its ads aren’t able to control you, being locked into Facebook will eventually pay off. “Rather than thinking of Facebook as a company that has figured out how to show you exactly the right ad in exactly the right way to get you to do what its advertisers want, think of it as a company that has figured out how to make you slog through an endless torrent of arguments even though they make you miserable, spending so much time on the site that it eventually shows you at least one ad that you respond to.”

Where Hwang focuses on the financial crises of 1929 and 2008 as a parallel to our current conundrum, Doctorow calls our attention to Robert Bork’s redefinition of monopoly, one that gives giant corporations a pass so long as consumers have some kind of individual benefit – a cheaper pair of shoes versus an economy where shoemakers can compete for business. “Bork was a crank,” Doctorow writes, “but he was a crank with a theory that rich people really liked.”

Doctorow does a good job of demystifying the power of algorithms to shape our perception. It’s the rentier economy, stupid. “Tech was born at the moment that antitrust enforcement was being dismantled, and tech fell into exactly the same pathologies that antitrust was supposed to guard against.” While we wring our hands about the impossibility of overcoming network effects, he argues it’s not a feature of tech giants’ platforms, instead it’s simply the power of monopoly that makes Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple so powerful. He points to how this is happening in industries of all kinds.

From professional wrestling to consumer packaged goods to commercial property leasing to banking to sea freight to oil to record labels to newspaper ownership to theme parks, every industry has undergone a massive shift toward concentration. There’s no obvious network effects or first-mover advantage at play in these industries. However, in every case, these industries attained their concentrated status through tactics that were prohibited before Bork’s triumph: merging with major competitors, buying out innovative new market entrants, horizontal and vertical integration, and a suite of anti-competitive tactics that were once illegal but are not any longer.

He argues this economic trend and its impact on lives, rather than supernaturally effective algorithms, has tilled the ground for our current dilemma of distrust in institutions and a willingness to believe in things that seem obviously factually untrue. “Conspiracy and denial have skyrocketed in lockstep with the growth of Big Inequality, which has also tracked the rise of Big Tech and Big Pharma and Big Wrestling and Big Car and Big Movie Theater and Big Everything Else.”

There are efforts afoot to pass legislation to make big tech more responsible: to filter better, to monitor and suppress hateful speech, to be less biased (which means totally different things, depending on your political persuasion). Doctorow thinks this is misguided, because it vests in these massive corporations the responsibility to police themselves over what should be public decisions, and it offers large companies an advantage. “All these solutions assume that tech companies are a fixture, that their dominance over the internet is a permanent fact. Proposals to replace Big Tech with a more diffused, pluralistic internet are nowhere to be found. Worse: The ‘solutions’ on the table today require Big Tech to stay big because only the very largest companies can afford to implement the systems these laws demand.”

In the end, he believes, we can either insist that big tech fixes itself, or we can fix the problems that made them big, but not both.

If you want to learn about the flaws in the programmatic advertising systems underlying the internet as we know it today, and why those flaws threaten the entire thing, Hwang is a good guide. If you want to think about the broader economic conditions that gave big tech so much power, Doctorow puts it all in perspective. Both recommend different forms of government action, needed urgently. Any form of regulatory reform may seem impossible in the face of our current polarization paralysis, but at least we can rest assured the claims for mass persuasion advanced by these companies are mostly hollow.

Barbara, who is the target audience for these two books? Who should the target audience be? Not me, since I’m only on FB to the extent that I was included in a post that a friend sent out about the death of her husband. If the target audience is our legislators, they seem unable to understand the extent and the implications of the situation you have summarized. Without massive education, which, given the multitude of obviously pressing problems, I don’t see anyone having the energy or the impetus to address these problems. I try, within my limited means and understanding, to inform friends and neighbors about what are, to me, important local and statewide matters. Who is able to reach out to those people so that they’re aware of what sounds like an impending crisis.

Hope that you are healthy and not too depressed by the current state of affairs. I just keep thinking of John Lewis’ advice and do my best to keep getting in good trouble.

What a great question! The Doctorow book is free online, but the site where it’s posted is mostly aimed at tech geeks. The Hwang book is published by Farrar Straus & Giroux, so it’s presumably not too niche, but … it’s pretty niche. Both of them are a little vague on how we’re supposed to actually make the changes they recommend. All of the books in this subject area say we need legislation and none of them can quite connect the dots as to how that can happen.

BUT … I am cheered in a way to hear strong arguments that these companies can’t actually accomplish what they say – target persuasion so precisely that people are rendered helpless against their persuasive powers. And both authors remind us that we responded to crises in the past with legislation – in the progressive era trusts were busted, in the New Deal banks were regulated. I found myself humming the old WWII song, “We did it before, we can do it again.”

So good to hear from you! Keep up the good trouble. You’re an inspiration.

I’d like to move this discussion a bit to libraries. When I taught collection development, one of my questions revolved around a quote by Pat Sajek who criticized the media for claiming credit for any good that resulted from their efforts while denying any bad effects. Students could then write an essay on whether the same was true for libraries. To give two quick examples, should parents who wish to impose a strict system of belief on their children be angry with the library for exposing them to other viewpoints? The library is part of the reason why I stopped being a Catholic and became an atheist. The second was an excellent paper from a student with the thesis that the colonial powers used libraries to destroy indigenous culture and replace it with Euro-centric beliefs.

The interesting part is that, when I presented this idea to several media people, they denied that what they did had any effect upon people. (One was on the Freedom to Read Foundation Board.) My rejoinder was to ask about advertising. If it influences peoples’ buying habits, it has an effect, If it doesn’t, the whole advertising industry is based upon fraud.

On a personal level, I consider myself, perhaps falsely, not much influenced by advertising without some rational confirmation from outside sources. Why should I believe anything from someone whose whole I idea is to get beyond my rationality to convince me to do something that I might not want to do and is designed only to help the advertiser? Wells Fargo presented ads on its wonderful customer service while being punished for cheating its customers. Advertising does work for me only when it tells me about something of interest that I didn’t know about.

Two final comments. Should the library worry about materials that present an inaccurate view of life? I use romance novels as my usual example because I’ve been seen the evidence that they become addictive for some readers. While a fictional case, Madame Bovary by Flaubert recounts the story of a profoundly unhappy woman. Since her life didn’t match the excitement and happiness that she read about in 19th century romance novels, she then took dangerous steps like an affair that resulted in her ultimate suicide. Second, while many kids who read succeed, some, like my younger sister, use reading to withdraw from “real” life with negative results. In these two cases, I’m not saying libraries should change but that libraries are as guilty of presenting only a positive view as many organizations that librarians criticize.

How interesting that you taught collection development – I took a course on it in my first semester of library school and still vividly remember Don Davis making the point that if we insist books can influence people for good, they can also do harm. Most of my classmates were resistant to that idea, but it’s so central to the everyday dilemmas librarians face, especially in public libraries where the community of readers is so broad and so much of trade publishing is commercial and far from fact-checked. I don’t think there’s much doubt that The Turner Diaries has inflamed people who want a white ethnostate and think a race war is on the immediate horizon. There’s no doubt Uncle Tom’s Cabin influenced the abolitionist movement. It was by far the most interesting course that semester and remains the one I think back on most often. This stuff is hard.

The debate about reading as escapism has a long history. I don’t begrudge people an interest in escapism. We all need some of that. That “Netflix and chill” need is real, though you can’t spend your entire budget on it. (In fact many public libraries don’t buy romance at all which seems extreme to me – Patterson is okay, but not a love story?) I found Catherine Sheldrick Ross’s long-term study of avid readers reassuring about the multiple benefits of reading for pleasure, eg developing empathy and seeing oneself recognized) and her book, Reading Matters, is great. I also like The Uses of Literature, which argues for aesthetic pleasure and enchantment against a purely critical approach. (It’s aimed at the serious litcrit crowd, but I’m there for enchantment.) At a more practical level, Nancy Pearl recommends a readers advisory strategy of adding a “stretch” book to the pile of books you know you’ll like because they are comfortingly predictable. That’s a nice middle ground of respecting readers’ preferences while encouraging discovery.

Another topic worth discussion: the history of encouraging “retailing” in libraries and the wide adoption of the latest marketing techniques without much critical thought. Do we really want to plant all those Facebook and Insta and Twitter tracking beacons that nobody uses on our websites just because everyone else does?