This is a talk I prepared for ChALS, a Swedish information literacy conference hosted at Chalmers University. Avancez!

This is a talk I prepared for ChALS, a Swedish information literacy conference hosted at Chalmers University. Avancez!

Thank you for inviting me to be part of this conference, and I appreciate your willingness to listen to an American who has not learned Swedish; my apologies.

I am speaking to you from southern Minnesota, in the north-central United States on land that was taken from the Dakota people of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ. Following a broken treaty and exile, it was settled by Europeans like my Norwegian grandfather as well as Irish, Germans, Finns, and Swedes. When I grew up I heard stories about pioneers, but not much about what happened to the people whose land was taken. Pioneer stories had a purpose: at best, they taught us the United States was a place many people from different backgrounds could call home. It also was a story about how we took something wild and turned it into farms and cities. Indians were part of a romantic, mythic past, not part of our modern history, or our present society. (Of course, the Indians didn’t disappear. They are still here, like the Sami people.)

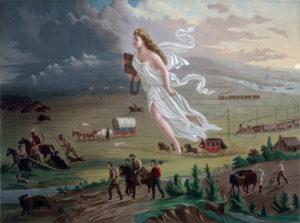

I grew up with misinformation about my country’s past, information kind of like this depiction of American Progress – a giant white woman bringing technology and modernization as Indians and wildlife disappear into darkness at the edge of the western frontier. This propaganda was included in manuals for Westward travelers and people wanting to settle on the stolen land.

I grew up with misinformation about my country’s past, information kind of like this depiction of American Progress – a giant white woman bringing technology and modernization as Indians and wildlife disappear into darkness at the edge of the western frontier. This propaganda was included in manuals for Westward travelers and people wanting to settle on the stolen land.

In fact, all Americans grow up influenced by disinformation that has been around for decades, even for centuries. Racism has deeply influenced our culture, and as sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom recently pointed out, white supremacy is and has always been a disinformation campaign. (Nicole Cooke also has some very smart things to say about this problem.) As soon as white folks began to kidnap Africans, the enslaved Blacks who built American fortunes were described in ways that dehumanized them to justify cruelty and exploitation. Much later, decades after the southern secessionists lost the civil war and enslaved people were given rights as American citizens, white southerners went on a campaign to strip away those rights. This not only involved acts of terrorism, it led to a campaign to erect monuments to the Confederate cause all over the United States, to visually alter how we understood our history.

Those monuments are finally in the process of being challenged and sometimes removed – as this monument to a Confederate general recently was – but not without a fight. This form of disinformation is a particularly difficult one to confront because it is so deeply embedded, and so many white people remain in denial that they might, themselves, have benefited from racism, but it’s one of the reasons we need to stand up for truth. Truth supports justice. We hope that by helping people recognize disinformation, whatever form it takes, we may contribute to a better world.

Those monuments are finally in the process of being challenged and sometimes removed – as this monument to a Confederate general recently was – but not without a fight. This form of disinformation is a particularly difficult one to confront because it is so deeply embedded, and so many white people remain in denial that they might, themselves, have benefited from racism, but it’s one of the reasons we need to stand up for truth. Truth supports justice. We hope that by helping people recognize disinformation, whatever form it takes, we may contribute to a better world.

And we have a big job in front of us today. We need to adjust our teaching to meet the challenge.

Part of the fun of being a librarian is helping people see beyond simple stories, helping them discover complexity and depth as they engage in meaning-making. We want students to feel they have the right to ask good questions of their own, and we want them to practice making sound judgements about the information they encounter. We help them become fluent with information resources and tools because it gives them agency and prepares them to participate knowledgeably in civic life. At its best, it’s education for democracy.

But what should that education look like today, when information is sought or, more often, encountered through social channels, at enormous volume and velocity? When popular platforms make it easy to craft disinformation that spreads more readily and further than good journalism? When instead of us seeking information, it seeks us? This is happening just as the common practice of outsourcing some of the work of making sound judgments to experts is breaking down under defunding, deliberate undermining, and widespread distrust of institutions. This problem is much worse in the US than in Sweden, but it’s a concern everywhere.

So this conference theme comes at a critical time. I came to my way of thinking some years ago during the three decades when I was a teaching librarian at a small college founded by Swedish immigrants. I was bothered by how we talk about information with students and about what we didn’t discuss with them when we talk about becoming information literate – which is to say, we didn’t talk much about the majority of information they encounter every day. While it’s important for our students to understand how our libraries operate so they can do their academic work, that doesn’t necessarily prepare them for a world where information flows through a diverse set of social channels whose workings are deliberately obscured. It doesn’t prepare them to make decisions about information at the speed of the web.

In 2019 I joined Project Information Literacy, an independent non-profit research institute directed by Dr. Alison Head, a social scientist who has designed and overseen a dozen major research projects for over a decade that focus on understanding undergraduate students’ experiences with information – for school, for their daily life, as they read the news, and how they use their information literacy skills after they graduate and go to work.

What we’ve learned is have trouble getting started with research projects. They tend to adopt a strategy and stick with it, seeking “safe” sources. They follow the news quite avidly, but don’t trust it. After graduation, they report they don’t feel their college education helped them learn how to ask questions of their own. And they are frustrated by the systems that invade their privacy, but feel resigned to using them.

The year I joined Project Information Literacy I was able to work on an exploratory study of what students think about the algorithms that are shaping their world – what they know about them and whether they have concerns. We learned about how some of them try to protect their privacy and how they feel about the “creepy” ads that follow them around, but also about how inadequate they felt their classroom experiences with media literacy were. As one student put it,

Usually, it’s like a two-day thing about ‘This is how you make sure your sources are credible.’ Well, I heard that in high school, you know, and that information is just kind of outdated . . . it’s just not the same as what it used to be.

In some cases they were simply told to ignore the web, which doesn’t do much to prepare people to be information literate.

We also learned, by interviewing instructors, that they were deeply concerned about disinformation, but they didn’t feel equipped to teach students about it – but they wished someone would.

All of this confirmed my sense that if we are serious about information literacy, we need to start talking about more than just how to seek and evaluate information for school projects, treating our expensive databases as a superior information shopping platform. We need to help think about information systems: the architectures, infrastructures, and fundamental belief systems that shape our information environment, including the fact that these systems are social, influenced by the biases and assumptions of the humans who create and use them.

Teaching students the technique of “lateral reading” is one relatively simple way to bring this kind of literacy into our teaching. Mike Caulfield, a director of blended and networked learning at a university in the western US, has argued our standard ways of providing media and information literacy no longer work. He believes what’s needed is learning how information works on the web. For decades we taught students to look closely at websites to decide if they are trustworthy. Looking for clues on individual websites doesn’t work in a high-velocity environment when we are bombarded with a continual flow of information that is often unattributed and emotionally triggering.

To create his heuristic he drew on findings from research at a history education group at Stanford University. Sam Wineburg and his colleagues assessed the skills of over 3,000 students and compared the ways they – and their teachers, trained historians – didn’t do what professional fact-checkers did. The fact-checkers engaged in “lateral reading,” checking other sources for context before spending time reading and analyzing a source. They were able to quickly dismiss disinformation, while the students and their professors mostly failed – very slowly. Because of the volume of choices we make continually online – should I believe this? Is it okay to share this? – learning how to make quick but sound decisions matters.

If you attended the morning sessions, you will already have been introduced to Nyhetsvärderaren (or The News Evaluator in English) which offers some great examples you can use with students to practice lateral reading.

This is a great tool to use in the classroom. It may actually undo some educational damage. The Stanford research group found students who made poor choices about sources often used things they’d been taught in school. They reasoned “it’s a dot com, so it’s not as good as a dot org.” They read the “about” information on a site rather than find out about the site from other sources. They said a site was trustworthy because it looks professional. This is all advice for website evaluation that still appears on many university websites – and it’s worse than useless. As a report from the group argued,

Any college or university that claims to prepare students for civic participation but fails to provide systematic instruction in web credibility is engaging in educational malpractice.

This Stanford group created a curriculum for civic online reasoning that includes lesson plans, slides, activities, and videos. Though they are US-centric, you might find useful ideas there. You do have to sign up for an account to see the materials, but they are free. They have quite a lot of material on the concept of lateral reading, as well as evaluating evidence and interpreting data.

Building on this concept of lateral reading, but wanting a method that could be taught and practiced quickly, Mike Caulfield came up with a much shorter, simpler curriculum based on four steps to take when judging information online. You might be able to make a decision after taking only two of the steps. He calls this SIFT:

Stop – pause before you hit the share button, especially if you have an emotional response to information. A lot of bad information is spread because it’s presented in emotionally resonant terms.

Stop – pause before you hit the share button, especially if you have an emotional response to information. A lot of bad information is spread because it’s presented in emotionally resonant terms.

Investigate the source – not by reading it closely, but by leaving the site and looking it up. Who is behind this publication? What is its reputation? Wikipedia can often provide those answers quickly. You could stop right here. Or move on to . . .

Find better coverage – If you’re still uncertain, leave the site and run a search on the topic. Perhaps a source you recognize as authoritative has covered the same news or topic. Perhaps you’ll find it has been fact-checked and rebutted. And if that isn’t enough to make a decision . . .

Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original source – If you are still unsure or really want to delve into it, check to see where the questionable source got its information and see if it’s describing it accurately of if it’s misrepresenting the original.

The point of all this is to be equipped to make good judgements quickly, without wasting time by looking for clues in a source that may be lying about its own purpose and credibility.

Here, for example, is a statement from an organization that sounds okay. Pediatricians, those are good people. They appear to take the stand that there are only two sexes, which are innate and immutable. They have a lot of scientific-sounding reasons for their beliefs. But rather than spending time trying to evaluate their argument, I’m going to do a bit of lateral reading.

Wikipedia has some information about this group. Oh, it’s a small fringe organization that has actually been designated a hate group. But it sounds so official!

It turns out there is another organization for pediatricians – much older, larger, and more professional and with very different policies about how to treat children who are non-binary. But it sure is easy to confuse the two! Which is probably intentional. I could go on and find better coverage, or I could stop here and simply dismiss this site as disinformation.

Let’s take a few minutes and try this technique. I’ll give you a screenshot of a source and see if you can use the SIFT method to make a judgement quickly. If you like, you can report out what you find. [Here, I showed a screenshot of a statement from the Heritage Foundation, and gave people half a minute to get some background on the organization and draw conclusions.]

This one is a little different. [Here I used an image found on page 16 of a SHEG publication that shows malformed daisies originally posted to Imgur] There isn’t an obvious source to investigate – it’s just some guy posting a photo and a comment. So in this case, you can jump to the third step and find better sources. Did nuclear radiation at the Fukushima power plant cause abnormalities in flowers? [People were given half a minute to search laterally and comment.]

That should give you a sense of how you could introduce this concept of lateral reading without it taking a lot of time. Mike Caulfield has plenty of examples on his infodemic.blog site. And don’t forget all of the useful material at Nyhetsvärderaren.

While these steps are designed for web information, the concept of lateral reading also applies to using scholarly and scientific information. Rather than read all the way through an article or study, find out what you can about the publication in which it appeared. Again, Wikipedia often provides a quick snapshot. Put the article’s findings in the context of related research: Is it an outlier, filling in a gap, or proposing something completely new? And of course it’s always useful to check the references an author has cited to get a sense of the ways ideas are networked, which isn’t something that’s always obvious to students used to the seeming simplicity of keyword searches. The networked, social nature of scholarship is worth making explicit. We librarians tend to want to simplify search and make it as easy as Google.

But by treating library databases as information shopping platforms that, like Google, appear to provide answers quickly and efficiently, we obscure how research actually works – just as Google obscures how it decides what is relevant and useful.

There are some limitations to the SIFT heuristic, and the most glaring one is in step three: it assumes we all agree on what a trustworthy source is without really going into what makes a source trustworthy. We are simply assumed to believe, for example, that The New York Times or perhaps Dagens Nyheter is a source of quality journalism. We don’t necessarily explain why we think certain publications are good and trustworthy, or how they operate differently from other less-respected sources. This basic knowledge may be a feature of Swedish education, which does a much better job of media and information literacy in school than the US. But I find the students I’ve worked with generally don’t know what journalism’s guiding principles are or what common practices are followed by good reporters.

And when I’ve talked with them about those principles, they often are skeptical. Thanks to the market fundamentalism that has so dominated economic and political policy for decades, many people have been brainwashed to believe that the major motivation for human behavior is self-interest, and that self-interest certainly is a design feature of the platforms where they consume media daily.

Let’s consider YouTube, for instance. Google is an advertising business that bought this video-sharing platform to expand its ad reach. YouTube is designed to keep people watching because they will be exposed to more ads, so videos with an emotional appeal are displayed when a video finishes. These appeals may be tied to fear, anger, or humor. Self-interest is built into the model, and it fuels the creation and spread of extreme material. People who contribute content are shown metrics that encourage them to see themselves as brands to be monetized. Because attention can be turned into money, people make guesses about the platforms’ algorithms so they can gain more followers, more views, more fame and sometimes fortune. The platforms benefit by having millions create ad-ready content for them.

These appeals may be tied to fear, anger, or humor. Self-interest is built into the model, and it fuels the creation and spread of extreme material. People who contribute content are shown metrics that encourage them to see themselves as brands to be monetized. Because attention can be turned into money, people make guesses about the platforms’ algorithms so they can gain more followers, more views, more fame and sometimes fortune. The platforms benefit by having millions create ad-ready content for them.

It works in reverse, too. A major reason that these platforms have become such toxic places is that their systems can be exploited by white supremacists, conspiracy theorists, and extremists of all kinds. The message-testing and personalization tools that were designed to sell things work quite well for selling ideas, and because we don’t see the same messages others see, it can be difficult to know that entire communities are being created and new members recruited to some very strange beliefs. Platforms that use algorithms to shape viewership have become sources of revenue and megaphones for people who are polluting the web with lies and hate.

Students have some understanding of how these platforms work because they participate in them and observe how different kinds of content are rewarded by the algorithms. They have much less opportunity to experience the ethical practices that underlie quality information. If the most common encounters you have with information come from platforms that traffic in self-interested persuasion, you might assume all systems that produce and share information are similarly designed to seek attention and sell ideas. This is why it’s important to shift our information literacy efforts from seeking and choosing information sources to discussions of what social practices make information good and how the systems we use actually work.

Let me take an example from a current crisis in my country. A sizeable percentage of Americans refuse to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Rather than take a vaccine that has been proven effective but which they distrust, they share information with one another which is amplified on partisan television shows that reach millions as well as through Facebook groups and other social media. Because they trust one another, but not medical science or the government, they are sickening themselves with horse medication and other strange treatments.

If we focus simply on judging the quality of information, we would point these people to better-quality information. But they aren’t distrusting the information; they distrust entire social systems that are used to make meaning. They have built up alternative methods of sense-making and have created separate knowledge networks that they turn to for information.

Oddly enough, while they don’t trust science or journalism or higher education, they do trust Google. They assume it is unbiased, simply a convenient way to do research and find answers stripped of any elitist influence. The “flatness” of Google search results makes the whole process appear somehow honest, non-judgmental, unlike the experts who they feel have lied to them.

What they don’t realize is that Google’s algorithms are just as prone to bias as we are. It, and other algorithm-driven systems, are shaped both by biased inputs and by engineers who see the world from a very specific position in society – one that is largely white, male, wealthy, and libertarian, one focused on profits, not truth. They also don’t know that the answers Google provides are deeply influence by the way we ask questions. Differently-worded search phrases about the same topic yield strikingly different results. As scholar Francesca Tripodi puts it,

The point of view from which an individual sees the world shapes the kinds of key words they chose when searching. These ideological fissures create multiple internets fueled by confirmation bias.

These fissures are exploited by people taking advantage of “data voids” – creating social issues, giving them unique names, and putting information about those issues online so those are the only results people find when they look for information using those names, at least until the press and responsible organizations catch up.

We owe it to our communities to help them understand how these systems operate. We’re not just dealing with a crisis of information quality, we’re facing an epistemological crisis. Education alone won’t solve the crisis of confidence in institutions, but it will give useful strategies to those who approach sense-making without inherent distrust of authority, who aren’t already deeply down the disinformation rabbit hole.

Since what I’m arguing for may require quite a lot of work, I owe it to you to provide some practical ideas of how to address our complicated information systems. Here are some ideas we’ve come up with at Project Information Literacy:

First, think about how information literacy can be framed as education for democracy. What do our students learn when we talk about information literacy? Are we equipping them to make good decisions about information as they go about their lives? This is a conversation to have with the instructors we work with: What ultimately is our purpose by asking students to do research? Where are the intersections between disciplines and public life and can we use those intersections to educate for democracy?

Second, let’s talk about what ethical beliefs and practices inform the creation of good information. Perhaps Swedish students learn these things, but I can’t say that happens in US schools. We tend to take a shortcut and say “trust these sources” but without explaining in some depth why. We should talk about how good information-seeking institutions sometimes fail, but avoid blurring the distinctions between the values and training of scientists, scholars, and journalists and the values and practices of social-media corporations, television personalities, and internet influencers. They are different, epistemologically and ethically, and those differences matter.

Third, the kids are alright, as we learned from conducting focus groups with over 100 students at eight diverse institutions in the US. As we delved deeper into the ways algorithms are being deployed in everyday life, from deciding who gets into university to who gets a job to how long a prison sentence is, based on obscure algorithmic processes, they got fired up, they wanted to make change. They also expressed grave concern about their elders and their younger siblings who they felt were especially at risk from algorithmic persuasion systems. Given a chance to learn and to share what they know, students could engage in community outreach that could be both helpful to communities and a powerful learning experience for students. If you have some kind of community learning program, this might be a good opportunity to spread valuable knowledge.

Finally, as librarians, I would urge us to step up. We heard from instructors that they didn’t feel equipped to teach about our current information environment because they didn’t understand it. As information professionals, we should provide leadership where there is an obvious gap. We can at the very least educate ourselves and look for places where this kind of information literacy fits. We can also call on local experts and convene conversations about these issues. Sometimes simply being the common ground for community learning is the best role a library can play in promoting this kind of learning. Whether it’s lessons in lateral reading or deeper explorations of why to trust and how we know, this is education for democracy.

This is fantastic!! Wonderfully stated and such an important focus for us social studies teachers. Thank you for this important talk. I’ll be sharing it out now!

Great article, I’d add that universities should be providing the wide base knowledge against which new ideas or concepts can be tested, the ‘I don’t believe science’ needs to be shown to be false early. I also wonder about the curatorial role of libraries and how we can use that role to help illustrate the trustworthiness of information sources beyond the walls of university content.

Yes, a knowledge base and an understanding of how we arrive at that knowledge base. What do humans do to figure stuff out? How do they avoid misleading themselves or fudging results? Without understanding these human processes, I’m not sure information by itself is enough.

when we talk about misleading ourselves we’re rapidly heading for the world of Kahneman, and I think his ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ should be required reading for almost everyone!