The New York Technical Services Librarians, an organization that has been active since 1923 – imagine all that has happened in tech services since 1923! – invited me to give a talk about bias in algorithms. They quickly got a recording up on their site and I am, more slowly, providing the transcript. Thanks for the invite and all the tech support, NYTSL!

The New York Technical Services Librarians, an organization that has been active since 1923 – imagine all that has happened in tech services since 1923! – invited me to give a talk about bias in algorithms. They quickly got a recording up on their site and I am, more slowly, providing the transcript. Thanks for the invite and all the tech support, NYTSL!

The Bigot in the Machine: Bias in Algorithmic Systems

Abstract: We are living in an “age of algorithms.” Vast quantities of information are collected, sorted, shared, combined, and acted on by proprietary black boxes. These systems use machine learning to build models and make predictions from data sets that may be out of date, incomplete, and biased. We will explore the ways bias creeps into information systems, take a look at how “big data,” artificial intelligence and machine learning often amplify bias unwittingly, and consider how these systems can be deliberately exploited by actors for whom bias is a feature, not a bug. Finally, we’ll discuss ways we can work with our communities to create a more fair and just information environment.

I want to talk about what we mean by “the age of algorithms,” and about how bias creeps into or is purposefully designed into algorithmic systems using examples in public health surveillance and in law enforcement. We’ll talk about how racists exploit the affordances of these systems to pollute our information environment. Finally, because I want to be hopeful, we’ll talk about some of the ways people are apply anti-racism to address the bigot in the machine and what we can do as librarians.

Let’s start, though, by thinking about how bias is inescapably part of any attempt to organize information. A few years ago, a colleague and I convened conversations with faculty at our college to tease out what they thought were threshold concepts in information literacy – this was just before the idea of threshold concepts entered into the discussions that resulted in the current Framework for Information Literacy – and one of our philosophy professors said something that speaks to this problem:

“information has to be organized and how it is organized matters.”

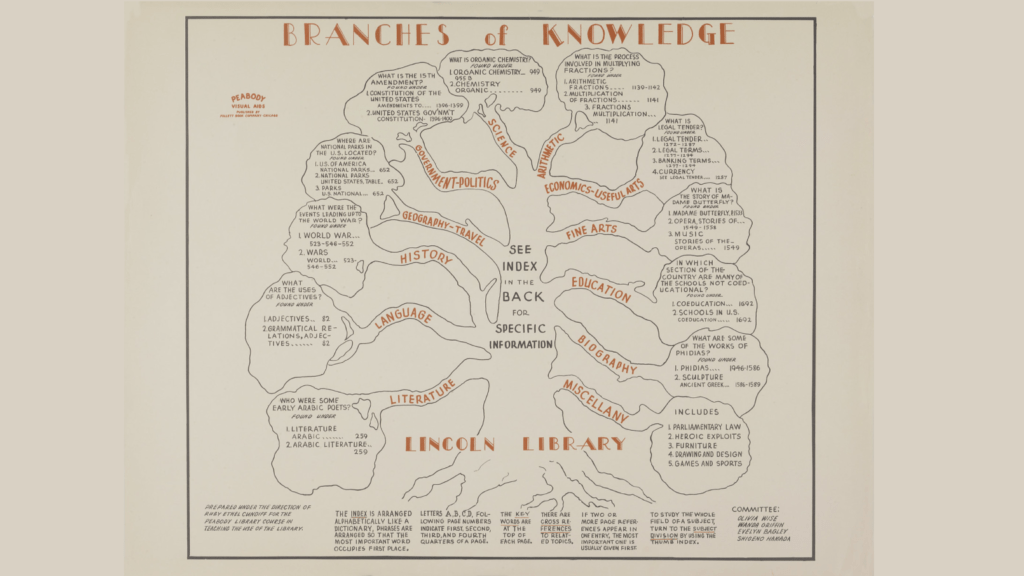

There’s an acknowledgement here that there isn’t any natural and universal hierarchy of knowledge. As librarians, organizing information is what we do, but we’re aware of how complex it is to try to name things and put things into categories without somehow shaping and defining how people experience that information – though we once thought categories could be settled, as this vintage poster illustrates.

As language shifts, we shift our subject headings, trying to “fix” the language so it is more accurate or less offensive. Though we may think of this as simply correcting mistakes, it is political work. We were reminded of just how political it is when Congress instructed its library, the one we count on to help us negotiate a common controlled vocabulary, not to fix the subject heading “illegal immigrants.” The bill used to halt that repair work had the popular title “Stopping Partisan Policy at the Library of Congress Act” and its Republican sponsor claimed this act would not only stop left-wing radicals from masking the threat posed by immigrants, it would save taxpayer money. Because apparently changing a subject heading is really, really expensive. Ironically, Tina Gross, a librarian who championed that change has saved much more taxpayer money by being one of four* tenured library faculty members at Saint Cloud State University who this year were “retrenched,” which is in itself an interestingly political word choice for “fired.” (This was not, I should add, directly related to her subject heading work, but it was a result of politically-motivated defunding of public higher education.)

As language shifts, we shift our subject headings, trying to “fix” the language so it is more accurate or less offensive. Though we may think of this as simply correcting mistakes, it is political work. We were reminded of just how political it is when Congress instructed its library, the one we count on to help us negotiate a common controlled vocabulary, not to fix the subject heading “illegal immigrants.” The bill used to halt that repair work had the popular title “Stopping Partisan Policy at the Library of Congress Act” and its Republican sponsor claimed this act would not only stop left-wing radicals from masking the threat posed by immigrants, it would save taxpayer money. Because apparently changing a subject heading is really, really expensive. Ironically, Tina Gross, a librarian who championed that change has saved much more taxpayer money by being one of four* tenured library faculty members at Saint Cloud State University who this year were “retrenched,” which is in itself an interestingly political word choice for “fired.” (This was not, I should add, directly related to her subject heading work, but it was a result of politically-motivated defunding of public higher education.)

As Matt Reidsma has pointed out, the challenges we face around names and categories is extended into discovery systems, which are trying to appear as “easy” as Google at surfacing relevant and useful information. Years ago he created this image of the “perfect catalog.”

Of course, without Google’s deep pockets for engineering talent and deep stores of data about who is searching for what, with our discovery systems we end up with a disembodied black box appearance of search results and recommendations which can be difficult for us to influence or explain – along with the faults that algorithms created by humans inevitably have. We keep the bias, but we lose the transparency we have with subject heading lists and classification systems as tools to examine and discuss those biases.

Of course, without Google’s deep pockets for engineering talent and deep stores of data about who is searching for what, with our discovery systems we end up with a disembodied black box appearance of search results and recommendations which can be difficult for us to influence or explain – along with the faults that algorithms created by humans inevitably have. We keep the bias, but we lose the transparency we have with subject heading lists and classification systems as tools to examine and discuss those biases.

Emily Drabinski, in her article “Queering the Catalog,” pointed out that we can’t really “fix” subject headings because language is not fixed, it’s fluid, and we can’t align it with what “the library user” expects because there is no singular user. She suggests, instead, that we approach all of this categorizing and naming from a critical perspective and use the library’s imperfect systems as an opportunity to help students interrogate all information systems. We want them to recognize that systems that seem automatic and universal are actually created by human beings, that biases in them are inevitable and can be revealed and contested. Increasingly, I would argue, we need to turn that learning opportunity toward understanding and critiquing the algorithmic systems that so dominate our age.

That concern shaped a recent research study. When I was invited to work with Alison Head and Margy MacMillan on a report for Project Information Literacy last year, we decided to inquire into how much college students and the faculty who teach them understand about how algorithms affect the information they seek and encounter as they go about their day, and whether they had concerns about it. In the introduction to that study, we described what we called for shorthand “the Age of Algorithms,” the combination of factors that shape our current information environment. I’m going to outline those briefly – and there’s an excellent graphic designed by Jessica Yurkovsky describing these points available for reuse at the project website.

That concern shaped a recent research study. When I was invited to work with Alison Head and Margy MacMillan on a report for Project Information Literacy last year, we decided to inquire into how much college students and the faculty who teach them understand about how algorithms affect the information they seek and encounter as they go about their day, and whether they had concerns about it. In the introduction to that study, we described what we called for shorthand “the Age of Algorithms,” the combination of factors that shape our current information environment. I’m going to outline those briefly – and there’s an excellent graphic designed by Jessica Yurkovsky describing these points available for reuse at the project website.

- We shed data constantly because we carry computers in our pockets that collect and share information about our daily lives, including where we go, who we associate with, and what questions we ask. It’s not just our phones; data is also being collected from our cars and household gadgets and health monitors.

- Advances in computation mean that data can be gathered, combined, and processed in real time. Being able to quickly manipulate enormous amounts of fine-grained, exhaustive data collected from multiple sources is new and big – and while engineers have this capability, we haven’t come to terms with it as a society.

- Disaggregation and redistribution of information from what used to be distinct sources, like articles published in a local newspaper, makes evaluation of sources more difficult, even as results are personalized using assumptions we can’t influence. We don’t all see the same information when we search and it’s not obvious where it came from.

- Automated decision-making systems are being applied to social institutions and processes that are being used to determine all kinds of things: who gets a job or access to social services. The bias that’s already present is being hidden inside a shiny black box, which makes it harder to confront.

- Artificial intelligence is “trained” using incomplete and often biased datasets, which means it can learn and amplify bias. This training is aimed at predicting the future but relies on records of the past.

- We’ve entered a new phase of late capitalism: the rise of the “attention economy” or “surveillance capitalism”— a profitable industry that uses vast amounts of “data exhaust” to personalize, predict and drive behavior. Because capitalism assumes human activity is centered on buying and selling, political persuasion has entered a whole new and very dangerous realm.

- These corporations have deep roots in Silicon Valley culture, which combines a reverence for wealth with a naïve belief in techno-solutionism that addresses unintended consequences with not much more than a public “oops!” and a promise of tweaking the algorithm. In the background, these companies – among the most profitable in the world – spend millions to lobby politicians to ensure they retain great power but very little responsibility.

- Finally, decades of media consolidation, deregulation, neoliberal economic policies, and the rise of a powerful right-wing media sphere combined with the rise of social media platforms that are designed for persuasion but have no ethical duty of care, have contributed to engineered distrust of established knowledge traditions such as science, journalism, and scholarship. We live in a highly destabilized knowledge environment where the idea of truth is a matter of politically-aligned consumer choice.

In our focus groups, we learned that students were very aware of the ways Google, YouTube, and Facebook collect information because they could see it happening in the creepy way ads followed them around the internet across devices and platforms. They were also aware of how what they saw on social media was influenced by algorithms that purposefully amplify personalized emotion-engaging messages for profit.

Most of them were indignant about their loss of privacy, but felt powerless because there seemed to be no way to opt out. What they knew about defending their privacy they had learned from one another, even taking notes during these focus groups as individuals described the defensive practices they use. But these were individual steps, they didn’t feel empowered to do anything collectively. They basically thought there was nothing that could be done.

As part of our focus group script, we asked about the ways algorithms were being used to evaluate college applicants, get a job or a loan, or even determine criminal sentences. Most were not familiar with these practices and were really bothered when they learned about it. As one student put it, these systems are

“just a fancy technology-enabled form of stereotyping and discrimination, which is inherently problematic, but it’s easier for us to overlook because it’s happening online and we’re not seeing it.”

Some students brought up some of the reports of bias in algorithmic systems that we’ve seen in the popular press for some time now: Washroom faucets that are essentially whites-only, because they weren’t designed to recognize dark skin; Google algorithms mistakenly labeling images of Black men as gorillas; Algorithms that place ads suggesting criminal background checks are recommended when searching for names that the algorithm suspects are African American. Though they had a wide range of awareness, they were deeply interested, and our conversations left them energized and hungry to learn more, which is a great sign and, I think, an opportunity we should seize. If we see ourselves as information professionals serving communities for the public good, this is clearly an area where there’s an opening for learning together.

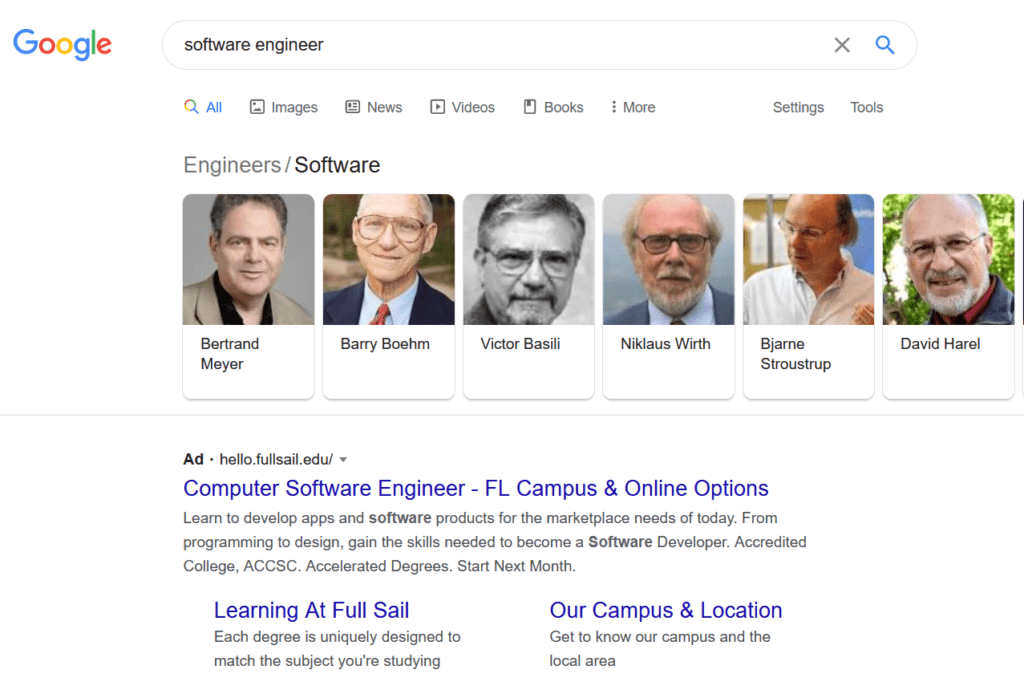

How exactly does bias enter into algorithms when engineers don’t intend it? As in these recent Google results captured on June 14, 2020:

Nobody designing faucets was actually trying to reenact Jim Crow laws segregating bathrooms. Google didn’t mean to insult Black people by calling them apes. But the big tech industry is dominated by people who simply don’t think about racism. They’re focused on technical issues and creating new products quickly. They care about market share and growth and raising capital and, while they make claims about how much their products improve the world, they know very little about the world or the problems they claim to be solving. They tend to base their assumptions on ideas of human behavior in individualistic, market-based terms. They work in an environment that is hostile to people who care about racism and sexism. Too often their deep ignorance about people unlike them is matched by their overconfidence. Ignorance is no excuse, and there are promising signs that tech workers are becoming aware even as their employers find that awareness threatening.

Let’s look at one example of how good intentions can go bad.

A provider of healthcare decision-making software that is used to manage care for some 200 million people each year wanted to create an algorithm that would flag patients who were likely in need of follow-up care after hospitalization. One set of data they used to determine need was how much money had been spent in the past on their care. The assumption was that everyone had equal access to healthcare. Yeah . . . no. Using this algorithm, less than twenty percent of the patients it predicted should have follow-up care were Black, but when researchers examined the underlying data they found that percentage should be closer to fifty percent. The algorithm failed millions of patients.

This was discovered by independent researchers, and when raised the issue – what are you people doing? – the company worked with them to find different, more accurate data to use in their predictive model. But since these systems are proprietary, it’s rare for anyone to be able to reverse-engineer the underlying assumptions. This is not to say algorithms are more biased than human decision-makers. What it means, though, is that an “honest” mistake can affect millions of people, and the reason for the mistake is hidden behind an appearance of objectivity, of scientific precision. An awful lot of money goes into outsourcing the work of making decisions to technology companies. Of making what were human acts into data-driven and automated processes. Currently, there’s not a lot of accountability for those decisions, and little risk to the companies themselves when they make mistakes.

Right now, during the most deadly pandemic of a century, we’ve been seeing a lot of discussion of using technology to cope. That can take the form of universities hiring companies that conduct invasive exam proctoring for students, or employers keeping watch over their workers at their homes in extremely intrusive ways, or companies using facial recognition and location-and health-tracking apps to check for social distancing, mask-wearing, and health conditions. Hospitals have used AI to predict which COVID patients needed the most care, or were less likely to benefit from care in a triage situation, without having any way of knowing if the algorithms actually work. These technologies are being rolled out quickly, trained on historical data in a world dealing with a new and unpredictable disease. And, as we learned from our experience after 9/11, once surveillance is used to solve one crisis, it’s very difficult to uproot.

A good example of how the bigot might unintentionally saunter into the machine is in efforts to automate the work of contact tracing. I mean, all that data is already available, right? We know where everyone is and who they’re near. All we need to do is write some code to organize that information so that everyone who has come in contact with an infected person is informed and sent a notification about how to stop the spread. But it’s not so simple.

First, there’s an interoperability problem. Most phones run on one of two incompatible systems, Apple’s IoS and Google’s Android. No worries, those two companies have agreed to work together. But there’s another problem. People have become alarmed about invasive surveillance. A convincing argument can be made that privacy during a public health emergency should not be viewed as an absolute right, that with proper safeguards a communitarian concern for everyone’s collective welfare in a pandemic takes priority over individual privacy. However, distrust of technology, government, and science is so deeply embedded in American society right now. A survey conducted by the Washington Post in late April found that three out of five Americans would be unable or unwilling to use such an app, which would make it ineffective. The damage wrought by tech companies cavalierly seizing our data aided by lax regulation and deliberately confusing click-through agreements is coming home to roost. Given a choice, a significant portion of the public rejects automated public health surveillance, even if it may cost lives.

There are other problems with rolling out a an app to automate the work of contact tracing, issues technologists might overlook. As Cathy O’Neil has pointed out, the people who are most at risk are the least likely to have smartphones, healthcare, financial support available, or even a place to go if they find out they are infected. And as Julia Angwin argues, the app design that Google and Apple seem to be working on would emphasize personal choice using proximity marketing tools – Bluetooth and beacons – in a way that would make it vulnerable to trolls and spoofers. Given how political pandemic response has become, an app like this could be easily vandalized.

Apart from these challenges, there’s something more significantly wrong with assuming smart phone technology can largely replace traditional contact tracing. The job is not just about locating people and their contacts, it’s about relationships, about taking the time to build trust and help people come to terms with a frightening situation. Contact tracers have to be able to find out what needs people have and be able to organize support for a wide variety of life situations. This is human work. Tech companies can figure out who some of us have come in contact with. They can’t do any of the rest of the job.

The temptation to outsource labor to algorithms rather than count on public health professionals to organize work they know how to do is just another way to overlook systemic racism and its effects. Like every other technology, contact tracing apps are more about politics and social structures than about code.

I want to turn to another technology topic that is on our minds right now, and a natural segue is a comment my governor made about how law enforcement officials were using local, state, and federal resources to “contact-trace” people arrested in the uprising after George Floyd was murdered by police.

When I heard him say that, my jaw dropped. I know tracing connections among people has been a common strategy in law enforcement, and that strategy has been ramped up with technology, but I’d never heard that practice described with a phrase associated with disease containment. It’s a statement about our priorities that we can’t seem to coordinate nationally or fund the contact tracers we need during a pandemic, but we can allow police operations to consume a huge portion of city budgets and coordinate with state and federal intelligence agencies.

So, how do artificial intelligence, machine learning, and algorithms amplify racism in policing? Well, first let’s acknowledge racism is a persistent problem in all aspects of what we euphemistically call “criminal justice.” Police departments were established in the mid-nineteenth century to control urban populations and defend the interests of the propertied class. In the south, slave patrols provided the template for the development of police organizations. Protecting property and controlling the propertyless has always been a focus of the job, which has become more militaristic in recent decades. In the 1960s the first SWAT teams were created specifically to bring military tactics to the handling of riots that erupted in response to racism, riots often sparked by acts of police brutality. In the 1990s the military began a program to pass its surplus material to local police departments. Since 9/11 police departments have had access to even more military equipment as well as intelligence agency technologies. The military equipment police use underscores the impression that their job is not to serve and protect, but to control and subdue the populace in ways that affect every aspect of Black lives. It’s worth noting a 2017 study found police departments that received equipment transferred from the military were more likely than those that hadn’t to kill people. We know Blacks are more likely than whites to be at risk of being killed by police, and those killings and other police violence have a ripple effect on the health and wellbeing of entire Black communities.

There are interesting connections between the militarization of policing and their uses of surveillance technology. In the 1960s Lyndon Johnson engaged a technology company created by an MIT political scientist that had used computers to fine-tune political messaging for the Kennedy campaign and asked to develop predictive programs to identify trends and name leaders in the neighborhoods where riots had occurred.

That was the start of automating police surveillance capabilities, which ramped up enormously after 9/11. Now there are 80 “fusion centers” across the country that bring local police, federal agencies, the military, and private industry players together to gather and share information – all in great secrecy. This kind of cross-agency secret surveillance was outlawed after Watergate, though it never really went away. The response to the 9/11 attacks made it official policy and billions of dollars went into creating this network, which has come up with some bizarre ideas, such as a Texas fusion center warning that Muslim civil liberties groups, peace activists, and hip-hop bands were conspiring to impose Sharia law and another in Virginia instructing law enforcement to be alert to universities, especially HBCUs, being “nodes of radicalization.” Note the racism in these “alerts.”

The role technology companies play in bigoted policing practices has become mindbogglingly massive and profitable. The war on terror has given way to the war on immigrants, with all kinds of sophisticated technologies being deployed in the name of national security. I was shocked and a bit dubious when someone tweeted that a predator drone had been deployed from its routine flight path along the Canadian border to circle the Twin Cities during the protests there, so I went into fact-checking mode, wanting to avoid getting sucked into tinfoil hat territory. But no, it was real. The state asked for a predator drone to provide aerial surveillance of the city and communicate with police on the ground in real time. These drones, and other military aircraft, have moved from the battlefield to a 100-mile zone within our borders, and now are surveilling our cities.

Police have been using all kinds of digital surveillance technology – including license plate recognition systems, facial recognition software, predictive policing algorithms that purport to tell them where crime might happen and who might commit crimes, and cell tower simulators, which gather cell phone identifiers and associated data from all the phones in the vicinity. All of this tech is developed by private companies with proprietary software that cannot be examined. In the case of cell phone simulators, the technology is so secret the FBI insists local law enforcement signs a non-disclosure agreement and have insisted that prosecutions be dropped if it might disclose use of this technology. There is evidence Minneapolis police used Clearview AI, which scraped billions of photos from social media against the terms of service and has staff with ties to neo-Nazis and white nationalists. Basically, all of these policing products means that police can pay private companies to do things that it would be unconstitutional for the police to do themselves.

Additionally, the pools of information collected about us to sell ads can potentially be used by police to find out who was where. For example, digital display ads on bus stops in Minneapolis were able to collect digital IDs for every phone nearby. Altogether the surveillance capacity of local law enforcement, in partnership with state and federal agencies, is frighteningly vast – and the cost of all of those technologies is part of why police budgets consume so much of the public’s investment in their cities – though much of the most sophisticated software is underwritten by Homeland Security, also paid for by us.

There has been a lot of coverage of these issues since the current Black Lives Matter uprising, but African Americans have technology used against them all the time. Ruha Benjamin calls this “the new Jim Code”:

“the employment of new technologies that reflect and reproduce existing inequalities but that are promoted and perceived as more objective or progressive than the discriminatory systems of a previous era.”

Increasingly public services are being automated in ways designed to deprive the poor from benefits. As incarceration goes online, people pay to be monitored by tech companies rather than meet with parole officers. And since policing itself is disproportionately devoted to containing a “risk” it sees in Blackness, the technologies that may be shocking to many white protestors are a daily reality for Black and Latinx people, surveillance running in a straight line from slave patrols to artificial intelligence.

Finally, let’s talk about another feature of our technological environment: all that data collected to advertise products is used to manipulate people, to influence people’s beliefs. White supremacists are very good at using these tools to find and groom potential recruits – often providing what appears to be a caring, supportive community to disaffected young men, offering them social connections and what seems to be affirming life advice as they draw them into the fold. They strategically use a ladder of technological social spaces, starting with obscure ones that are virtually invisible to the average person where they test and shape messages that can be migrated up through other social channels and pushed into the rightwing media sphere and, once the president or other prominent officials have adopted those messages, into the mainstream press. This is a deliberate strategy to shift the Overton Window to make totally unacceptable ideas seem suddenly up for debate.

There is compelling research about how this works. Jessie Daniels pioneered the idea that white supremacists have embraced new media and, especially, the internet to amplify and spread their message in her 2006 book, Cyber Racism. Since then, she has documented ways racists have used social channels and internet culture, which spreads ideas through memes that offer plausible deniability if attacked as racist. Oh, that’s just a joke, can’t you tell? Their messages have been embraced by the president, who has pressured social media companies to allow extremist speech by claiming without evidence that Twitter and Facebook censor rightwing viewpoints, which has only encouraged Facebook’s tendency to resist taking any responsibility for incendiary hate speech.

There’s loads of great research on this subject, but I’ll just highlight a couple more books. Yochai Benkler and colleagues have shown that new technologies build on an already highly developed rightwing media sphere established in the late 1970s, built by popular talk radio stars and Fox News. What their research shows is that conspiracy theories and extremist positions fail to take root with the left wing audience because they value traditional journalism and fact-checking. Rightwing audiences value their entire coherent belief system above mere facts and are likely to reject a claim unless it fits into what they already believe, is consistent with their cultural identity. While social media audience targeting has amplified this asymmetry, the foundation for our present epistemic crisis is found in earlier forms of media after they were deregulated – radio and television.

Finally, research by Jen Schradie documents why the right is winning the internet. It’s not just that a few clever strategists really get how to use Facebook, but that the left is more fragmented, more prone to be critical of itself, and less focused on gaining political power. Moreover, despite the amount of press attention devoted to the plight of disappointed white men who are drawn to Trump, poor people on the left are much less likely to have access to technology and be in contact with well-funded movements.

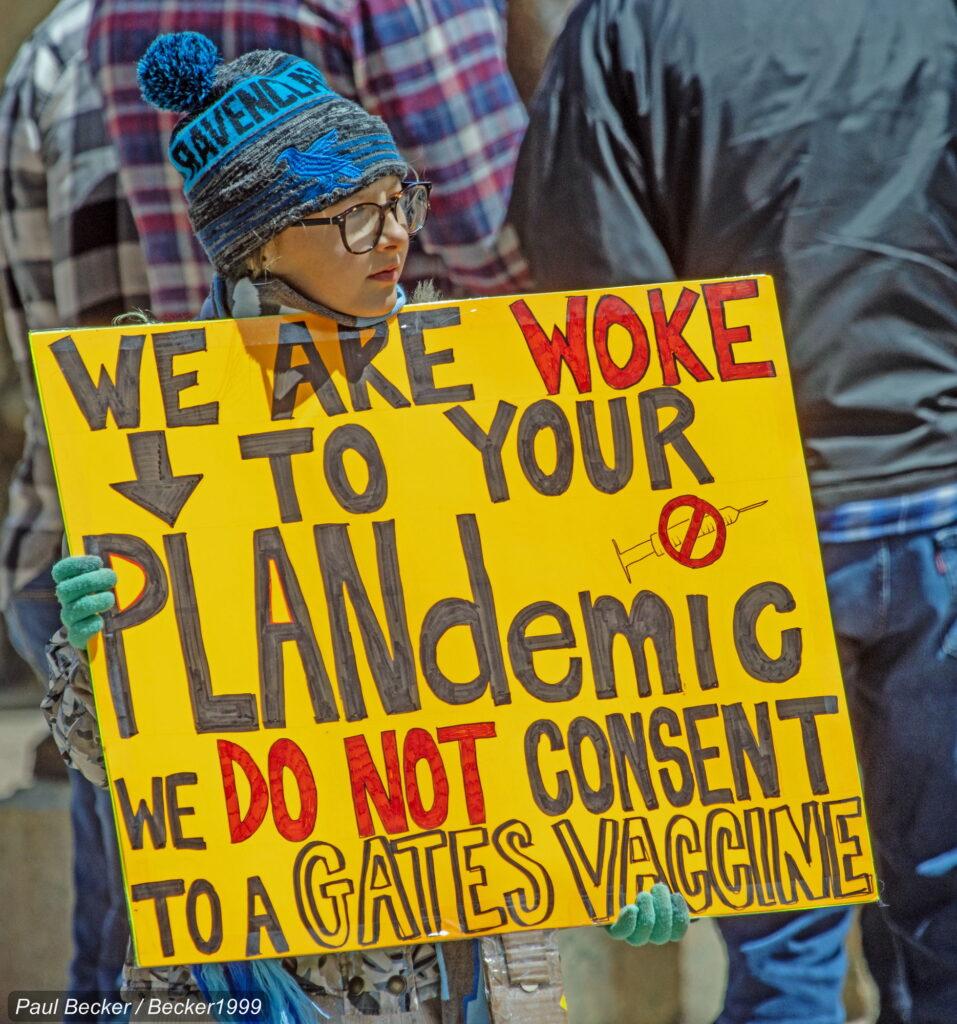

Let’s see how this is playing out in our current crises. The World Health Organization recognized an infodemic was arising in parallel to the pandemic.

Soon after the world was alerted to this new coronavirus, a weird conspiracy theory began to spread, tying Bill Gates to the disease. By mid-March various strands of rumor coalesced into a single narrative: Bill Gates was planning to microchip us all by planting high-tech spy software in a vaccine. A YouTube video, viewed two million times, was transmitted to a wider audience when Roger Stone promoted it on a radio show, and then it was reported by the New York Post which didn’t debunk the claim. This news story was liked, shared, or commented on at Facebook by a million people, which is more than usually react to a more mainstream news article.

One study that looked for patterns in the spread of Covid disinformation concluded a “hate multiverse” was seizing on the pandemic to associate it with their agendas, blaming it on Jews, immigrants, Asians, and the “deep state.” Though YouTube and Facebook have bent over backward to avoid being seen as censoring conservatives, they did do more to curb disinformation about the pandemic than we’ve seen before. Still, a carefully orchestrated social media plan pushed a slickly-produced conspiracy video out to millions of viewers, sowing doubt about basic medical facts, before it could be quarantined.

In the case of the uprising, the administration has decided to blame Antifa – anti fascists who are not organized in any central way – for any violence that has happened and the president has declared it (on Twitter) a terrorist group, without a factual or legal basis. This developed in parallel with a peculiar panic attack that swept across the internet and into racism-enabling apps like NextDoor and Ring, amplified by police departments, rightwing media, and also by the president’s son on Twitter. Suddenly people in small towns across the country prepared for busloads of anti-fascist terrorists to descend on their communities to wreak havoc. It all started, apparently, with a tweet sent by a false account set up by Identity Evropa (now calling itself the American Identity Movement), a white supremacist group. Using agents provocateurs is, of course, a long-standing strategy by police who routinely infiltrate leftwing groups to sow division and start trouble that can result in arrests. Now it can be done on a global scale and its origins can be difficult to trace. As Joan Donovan has shown, the same fake social media accounts that spread COVID-19 disinformation are spreading false and inflammatory rumors about the current uprising, and they are quickly rising right to the top, into the president’s Twitter account.

So we’ve seen how algorithmic systems amplify bias – either by starting with biased data and clueless assumptions, or by designing systems that are open to manipulation. What can we do about it?

First, let’s recognize what’s hopeful about this moment. Because we saw the murder of George Floyd on camera, because a teenaged girl had the courage and presence of mind to record those terrible eight minutes and forty-six seconds, a large majority of Americans, according to polls, clearly see the connection between racism and our militarized policing practices. I worry our attention, so trained by the attention economy to be easily distracted, might slip. But there’s a powerful combination of two trends happening right now: a greater understanding of how white supremacy operates and a growing sense of dissatisfaction with the giant tech corporations as instruments for surveillance and the propagation of hate. Though the students we talked to in focus groups in the fall of 2019 felt powerless to change big tech, just talking about it for a half hour made them eager to learn more and to take action.

Fortunately a generation of activists, especially young people of color, has honed their organizing skills and are prepared to lead change. A good example of citizen activism is the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, which is a grassroots community organization in Los Angeles focused on dismantling predictive policing technologies as a harm reduction strategy and a step toward abolition. This group has spent years researching, exposing, critiquing, and challenging police surveillance technologies such as PredPol, a predictive policing algorithm. In their words:

Predictive Policing is rooted in war and occupation. It is yet another tool, another practice built upon the long lineage including slave patrols, lantern laws, Jim Crow, Red Squads, war on drugs, war on crime, war on gangs, war on terror, Operation Hammer, SWAT, aerial patrols, Weed and Seed, stop and frisk, gang injunctions, broken windows, and Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR). However, this time it’s the veneer of science and technology, algorithms and data processing, hot spots, and math that give the Stalker State the power, justification, and supposed right to predict, to pathologize, and to criminalize whole communities, and to trace, track, monitor, contain, and murder individuals. This is the trajectory before the bullet hits the body.

StopLAPDSpying have researched the technologies being used by police and have won a number of lawsuits. Their most recent victory: LAPD announced it will stop using PredPol software. They are adamantly abolitionist and will go on working to end the carceral state.

And another example: The Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology (or POST) Act was introduced in New York City in 2018. This simply would require the NYPD, the largest police force in the country, to let city legislators and the public know what technology they are using and how it is used. They and the tech corporations who supply it have fought it tooth and nail. It now has enough sponsors on the city council to override a veto. It doesn’t seem too much to ask, yet it has taken years of struggle to get here.

Another example of how long-term hard work is beginning to pay off: Mariame Kaba, who you might know as @prisonculture on Twitter, has been advocating for prison abolition for years. Not reform, abolition. She recently wrote an essay for The New York Times about police and prison abolition that would be helpful to share with those who are puzzled by the concept.

The Minneapolis city council adopted a veto-proof resolution to essentially abolish the MPD. It will take time to work out the details and the city’s residents will have to vote for it, but would we even be here without that long-term groundwork Mariame Kaba has done?

Additionally we’re seeing, in the past year or so, technology workers resisting the work of building oppressive surveillance systems, of cities beginning to ban facial recognition technologies, and in the past week some of the companies that have built these systems saying they will either stop or will reexamine their business deals with police departments and, while I’m skeptical, it is at least a measure of how worried they are about public pressure.

Basically, this work is hard, it takes years, it takes finding and lifting up those who know how to do it. It takes imagination to realize another world is possible. The most effective leaders know history and have the imagination to believe things can be different. Libraries are in a position to help nurture and grow that kind of learning even as social programs are defunded and educational institutions strip away the humanities.

I keep hearing people say “police are asked to do too much” – to deal with homelessness, to deal with people with untreated mental illness in crisis, to “be social workers.” This sounds very familiar to librarians. Since we don’t have a functioning political system to address problems like homelessness, addiction, lack of child care, lack of access to health care, increasing poverty, all of the predictable outcomes of extreme inequality, we like to say “go to the library. We have the internet! We have Narcan! We’re here to help!” It’s good that we want to step up, but we need to do more to form coalitions to advocate for solutions to these problems rather than point to library programs as feel-good public relations. We shouldn’t pretend we can fill those gaps. This comes full circle when public library workers reach the limit of their capacities – and call the police. We need to support efforts to restore justice and dignity for all, and library-washing social failures is only a stopgap, not a solution.

We also need to join efforts to rein in the power of big tech, not just to oppose their oppression through policing and other surveillance algorithms but also to challenge the ability of a handful of giant monopolies to profit from the amplification of hate without accountability. When so much of the information we use in everyday life is mediated through platforms that have become the most profitable in the world by claiming our data to build an architecture of persuasion, that architecture does work that is the opposite of what libraries do – provide collective access to knowledge for the public good. The fact that libraries still exist and are still beloved by the public is proof alternatives are possible. We need to actively call for accountability and work with others to imagine socially responsible alternatives.

In our own libraries we need to move from celebrating diversity to practicing – and I mean practicing, over and over – anti-racism. We have to move beyond merely understanding racism to doing something to reduce its harms. As part of that work, we need to critically examine our own structures, and how our organizations might strengthen or stifle critical approaches to how we organize our own work. There’s a reason we are an 85 percent white profession. Let’s call it what it is: racism.

There are information needs that fall squarely in our job descriptions. Not just book recommendations and Libguides – those are fine, but they don’t necessarily lead to action. (This sarcastic tweet caught my eye.)

What could be more helpful is to be familiar with and have ready to hand links to relevant scholarship when issues arise. Strategically amplify what we already know about technologies that have the capacity to discriminate thanks to the work done by scholars – many of them women and people of color – that have been working on these issues for years and have the receipts. Send those links to reporters, policy makers, activists, and CEOs. I love making library displays but a lot of these folks never come into the library, and sending one on-target source can do a lot more good than compiling a fifty-tab Libguide.

What could be more helpful is to be familiar with and have ready to hand links to relevant scholarship when issues arise. Strategically amplify what we already know about technologies that have the capacity to discriminate thanks to the work done by scholars – many of them women and people of color – that have been working on these issues for years and have the receipts. Send those links to reporters, policy makers, activists, and CEOs. I love making library displays but a lot of these folks never come into the library, and sending one on-target source can do a lot more good than compiling a fifty-tab Libguide.

I also really like the work Alison Macrina has done with the Library Freedom Project. Training librarians around the country to help their communities learn about privacy and how to protect it is a very concrete way that librarians can live out a value that’s important to us, not because privacy by itself is a virtue but because it enables freedom. Leading a privacy workshop is a way of showing your community whose side you’re on while opening up space for something the public is truly concerned about. As Macrina has put it in a recent interview with Logic Magazine,

“Privacy is important, but what we’re really talking about is the newest frontier of exploitation by capital… with all of this work, I’m really trying to force a conversation about who controls the internet and what that means for our lives.”

The time seems right for our profession to make sure these conversations are happening, and to help those who are concerned to connect with the activists and organizations that are doing something about it. We can’t stop now. It will take all of us, and all our strength, to grab hold of the arc of history and bend it, ever so slowly, toward justice

*Edited: I originally wrote three librarians were “retrenched.” It was four, with a total of eight tenured faculty who were fired, er, retrenched. Unfortunately more cuts are coming.

Image credits

- Surveillance cameras by Jonathan McIntosh on Flickr

- “Tree of Knowledge” poster – photo by char booth on Flickr

- “perfect catalog” image by Matt Reidsma, used by permission

- George Floyd memorial – Photo by munshots on Unsplash

- State police deployed in Minneapolis – Photo by Tony Webster on Flickr

- National Guard solider in Washington DC after 1968 riot – photo by Warren K. Leffler on Wikimedia Commons

- Property under surveillance – Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

- Man holds deplorable and Pepe sign in St. Paul – photo by Fibonacci Blue on Flickr

- Child with “plandemic” sign – photo by Paul Becker on Flickr

- Site of announcement where Minneapolis city council defunded police – Photo by Tony Webster on Flickr

- Large protest in DC – photo by Ted Eytan on Flickr

This article needs a wider audience than librarians; NYT? (By the way, I graduated from UT in 1980!)

Thank you! Very kind of you to say. Maybe I’ll get a more broadly-focused draft together….

It may just be me, but the way this article was printed in this website seemed odd. The font is small, thin, and difficult for an older person with sight problems to read, and then when you are trying to emphasis something, which most people make a different color or bold face, it is in light grey, making it even more difficult to read. I struggled through, and although I have some differing opinions, having been a librarian since 1971, I do agree that we need to come together to make research of a topic clearer, and yet somehow safe guard our privacy.

Thanks for letting me know. I’ve looked for a WP template that is readable and thought this would do because the text is, at least, not gray. Amazing to me how hard it is to find readable website templates. But as you say, links don’t show up well because they go from black to … gray. I should really learn some CSS and roll my own.

…. and I did make some changes. It looks busier now, but the links are at least darker and more obviously links. (I hope!)

Thank you so much for this great article, it gives a lot to think about and hope! I’m a French librarian and we really need to address those issues here as well!

Are you aware of the Center for Humane Technology? I think you could partner with them to do some incredible work. 🙂

Thanks – I’m not that familiar, I’ll head over and take a look ….

I just came across this. Just wondering if you are aware of the the pioneering work of Safiya Umoja Noble (Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism) in this area?

Yes, it’s terrific, and an absolutely foundational work for understanding discrimination in algorithmic systems. Everybody, go read it!