I was invited to speak to librarians at the Lake Superior Library Symposium, a gathering of professionals from all kinds of libraries Up North. Since visiting Duluth is always a good idea, I was happy to be part of the conference program. The theme of the conference was Matter of Fact: Promoting Information Literacy in an Age of Fake News, so I glommed together a lot of thoughts I’ve had about the topic, speaking in particular about the place of libraries in the public sphere, why our values matter, and why it matters that those values haven’t been adopted by Big Tech. (Photo by Garrett Cumber on Unsplash.)

I was invited to speak to librarians at the Lake Superior Library Symposium, a gathering of professionals from all kinds of libraries Up North. Since visiting Duluth is always a good idea, I was happy to be part of the conference program. The theme of the conference was Matter of Fact: Promoting Information Literacy in an Age of Fake News, so I glommed together a lot of thoughts I’ve had about the topic, speaking in particular about the place of libraries in the public sphere, why our values matter, and why it matters that those values haven’t been adopted by Big Tech. (Photo by Garrett Cumber on Unsplash.)

Standing Up for Truth: The Place of Libraries in the Public Sphere

Thanks for welcoming me to this conference as we gather on traditional and current Ojibwe land. It looks like a terrific program. I’m honored to be part of it.

We librarians find ourselves in confusing times. In recent years, Americans have not only disagreed over facts, we no longer have a commonly-agreed on process for deciding what is true or false. While we’ve long debated the hot button issues that divide us – race, gender identities, what it means to be an American – beliefs about these issues have recently become entangled with our fundamental identities and our allegiance to one side or another of our deep political divide. These differences in how we decide what to believe, how we seek truth, and what it means for our sense of self has contributed to a crisis of democracy.

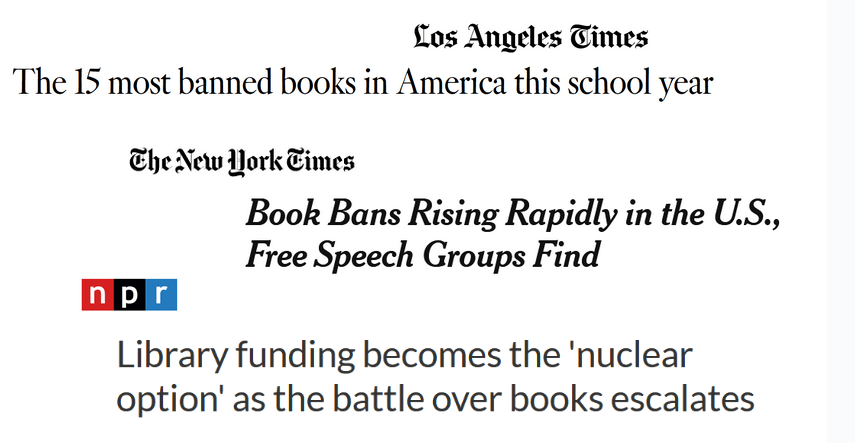

Though for a very long time, libraries were widely accepted as a Good Thing, regardless of our politics, we are suddenly right in the middle of this crisis. We’ve all seen the headlines.

Some of you may be living this experience right now, and I suspect all of you are thinking about how to respond if and when it does come to your library. It’s cheering that a solid majority of Americans reject censorship based on race or gender issues, but because this censorship movement is tied to the passage of oppressive laws, the targeting of vulnerable populations, and a troubling rise in the legitimization of violence for political gain, it’s a uniquely dangerous and unsettling moment. While this conflict over what should be on library shelves is about information – what information is valuable or dangerous, who decides, and who should have access – it’s about a lot more than that.

What I want to do today is talk about what libraries can do to defend democracy at this moment, and the fight against misinformation can be an important part of that. But it’s not enough to help people learn how recognize misinformation, vital though that is. Libraries practice democracy in a number of ways, including simply existing as a place that strives to serve everyone in our communities without trying to turn a profit. What a radical concept.

I want to reach back to how we arrived at the core values we hold today, and think about the ways every time we adopted one of them, it involved negotiating fundamental ideas about the place of libraries in the public sphere and how we help people seek truth. None of these principles came without conflict, which may help explain why libraries are currently such flash points. Second, I want to explore the current information landscape that lends itself to division, information sabotage, conflict entrepreneurship, and a hardening of positions. Finally, I want to point to the ways libraries already are small, local laboratories for democracy before we open discussion about how we can be more intentional about helping our communities become discerning about truth-seeking.

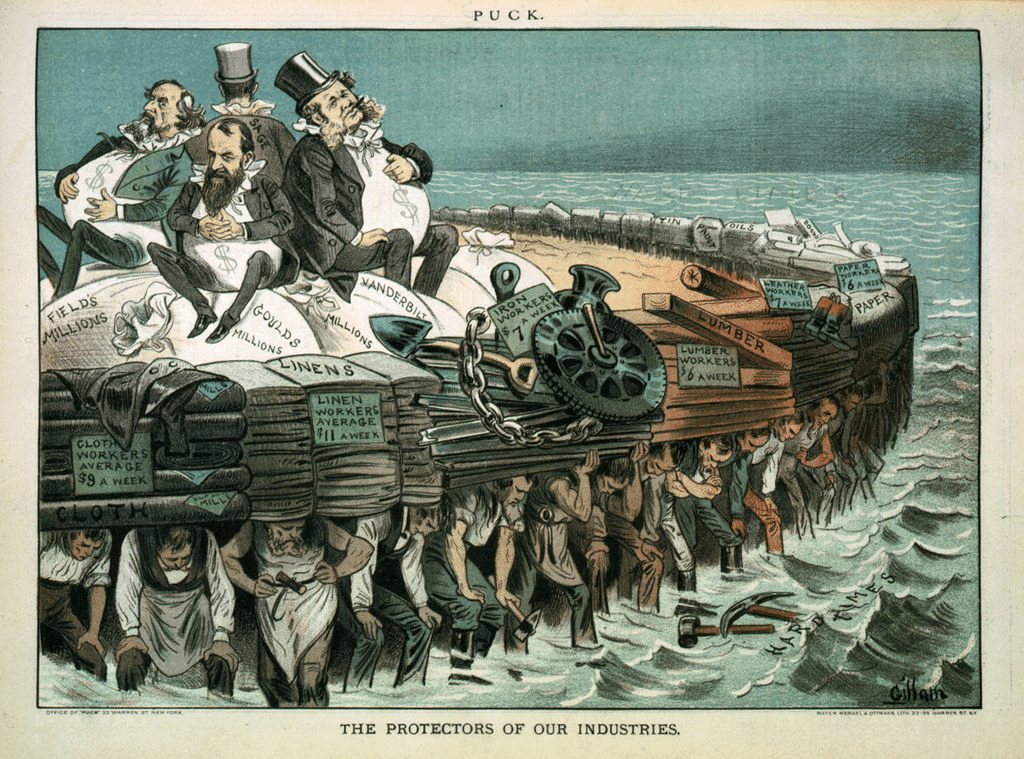

Let’s start with libraries’ very existence: If today we had to invent the public library, wouldn’t it seem impossibly idealistic? Yet the movement to establish public libraries arose during a time rather like ours, the first Gilded Age, when large corporations owned by the super-rich had the power to shape society.

Dubious global financial dealings and bank failures periodically roiled the economy. The gap between rich and poor grew, with unprecedented levels of wealth concentrated among a tiny percentage of the population. New communication technologies, industrial processes, and data-driven management methods combined, not so much to automate jobs as to automate human work under the watchful eye of management. There were more consumer goods on the market but increasing poverty.

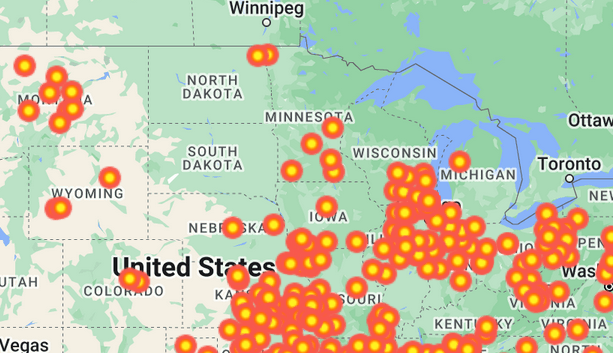

The changes weren’t all economic. Gender roles were changing as women began to live and work independently, and some objected, seeing it a threat traditional patriarchy. A wave of immigration altered national demographics. In response, native-born whites felt threatened, prompting a nativist backlash against immigrants, even as white southerners rolled back rights for Black Americans and the federal government began to fund the forced separation of native children from their parents and communities, attempting to eradicate indigenous culture in the name of “progress.” This map shows where Ku Klux Klan “klaverns” were founded in 1923.

So, we had extreme income inequality, new technologies altering the labor landscape, tensions over race and gender, and a political battle over who counted as American. It all sounds eerily familiar. But somehow, out of this froth of conflict the idea of the American public library emerged, a publicly-supported social and cultural institution that would be free to all.

But what libraries are for is a question that’s never completely settled. Take the oldest large public library, Boston Public, which has somewhat contradictory messages carved into its facade: not just Free to All, but also “The commonwealth requires the education of the people as the safeguard of order and Liberty.” Libraries were meant to stabilize the nation by forging a common culture, keeping order, while also promising liberty.

This dialectic shaped the ways librarians thought about their collections. Early on, many librarians pushed “improving” literature to elevate and educate the masses, and were frustrated by their patrons’ appetite for fiction, which they considered mind-weakening, destructive, and dangerously addictive. But popular demand won out, as readers insisted on shaping what Wayne Wiegand has called “the democracies of culture” that allowed people to make a variety of choices of their own.

Here I’m going to make a small detour. “Information seeking behavior” has been a standard part of our research for decades, and it undergirds many of our information literacy efforts, but in fact, a great deal of information is not sought at all, but rather encountered, some of it through social feeds, some of through other media, and some of it through fiction. Canadian LIS scholar Catherine Sheldrick Ross found, after interviewing hundreds of readers, that people find a wealth of meaning in what they read for pleasure: “reading permits the person to see into areas of society which otherwise would be denied to them and subsequently they are more able to participate fully in a democratic society.”

Of course, as with any information channel, fiction can be misleading. On the one hand, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a work of popular propaganda that used imagination to successfully advance the cause of abolition. On the other, we have the fact that generations of violent white supremacists, including Timothy McVeigh and Dylann Roof, have taken inspiration from The Turner Diaries, a fictional depiction of a race war that ends with the extermination of all non-white people from the earth.

Psychologist Richard Gerrig conducted experiments that suggested readers don’t distinguish information provided in fictional form from facts encountered elsewhere. The less readers know about the subject matter of the fictional work, the more likely they are to accept material in it as factual. Information, not sought deliberately but encountered in imaginative literature, becomes part of one’s knowledge base, for better or worse. Our brains don’t shelve fiction separately from non-fiction.

So the informational role of library access extends to fiction. But this issue – who decides what the library should have on its shelves – is never entirely settled. Just think about how every time someone alerts the public to a weeding campaign or a project to place little-used books in remote storage. Oh no! How dare those philistines attack culture this way! We negotiate this question of “access to what?” over and over, and balance different needs and interests, weighing the quality of the resources we choose while including patron involvement. That’s one way our communities engage in self-determination and libraries practice democracy.

What about intellectual freedom? There have always challenges to particular books, often triggered by a claim that certain books are immoral and dangerous. In the 1920s the Duluth Public Library had a “purgatory shelf” for books that had been challenged by “moral, upright, tax-paying citizens” who thought they were morally harmful, especially to minors.

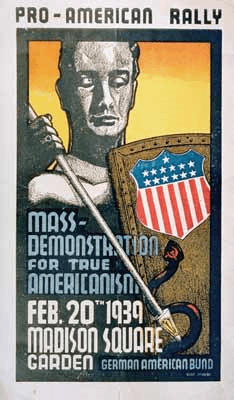

The ALA adopted the first version of the Library Bill of Rights in 1939, based on a document drafted by an Iowa librarian. It was an idealistic statement, and it wasn’t actually implemented, given that libraries in the south remained segregated until the 1960s, which the ALA failed to protest for decades. But it was a response to rising fascism.

The US was not uniformly opposed to fascism in the 1930s. We tend to forget that Nazis held a mass rally in Madison Square Garden, a Catholic priest used his popular radio program to preach antisemitism, an organization called the Christian Front plotted a violent insurrection, and a Minnesota senator was recruited by a Nazi agent to vocally oppose the US war effort. In that context, this statement opposing censorship and supporting access to a wide variety of viewpoints was courageous.

The Freedom to Read statement affirmed this stance in 1952 during Joe McCarthy’s anti-communism campaign. Though nearly everyone today condemns McCarthyism, he was a pretty popular figure – a 1954 Gallup poll found half of Americans had a favorable opinion of him – so this wasn’t necessarily an easy position to take.

And it was an interesting stance, given the findings of a massive study commissioned by the ALA to study the purpose and effectiveness of public libraries. Led by social scientists, the Public Library Inquiry in the late 1940s asked “How effective is the public library in cultivating intelligent loyalty to the basic conceptions and ideals of the democratic way of life?” It concluded not enough people used the library, and they weren’t the right people reading the right books. The authors recommended libraries double down on their educational mission and concentrate on supporting business interests and providing useful information to opinion leaders. As in the late 19th century, that advice met with resistance from the public – and from librarians. While we value democracy, we don’t define it in terms of loyalty.

Intellectual freedom and support for diversity, another library value, continue to vex us as we face challenges, especially now that these challenges are nationally organized and come with insults and threats of violence.

But in some ways, because libraries have negotiated these issues for decades, we are better prepared than many institutions to debate these challenges in public and defend our values. Though clearly these threats induce a certain chilling effect (as they intend to do), with the aid of experience and well-thought-out policies, we are standing up for a pluralistic, open-minded society.

Today, we are defending the right of kids to find characters like them in the books on library shelves and to oppose the erasure of people and their histories. But we also are finding a knee-jerk defense of free speech is perhaps more complicated than we thought. As bullies pick up the microphone and take over library spaces to say things that many patrons find hateful or threatening, we have to ask – whose speech are we protecting? Many folks have seen how school board and library board meetings can be co-opted by people whose speech drowns out discussion. Likewise, making a public meeting room available to groups who advocate hate for others could make entire classes of people feel threatened in the library.

This speaks to a tension in the US Constitution itself. The first amendment guarantees freedom of speech, and case law has ruled that we can’t discriminate on the basis of content, with some exceptions. But the fourteenth amendment guarantees equal protection regardless of race, religion, or even citizenship. Where speech rights interfere with equal protection, we have a conflict that has to be negotiated. And that’s an issue public and academic libraries grapple with all the time. We rely on our core values to guide us, but applying them is often really tricky.

Additional library values that we more or less assume these days include service, the public good, and social responsibility, that impulse from the progressive era that led to blending cultural improvement with social work. There is a historical gender angle to all this.

As public libraries spread across the country, they were often championed by women’s groups. Women’s clubs eventually were responsible for starting as many as three-quarters of the nation’s public libraries. Socially progressive work was aligned with the Victorian notion that men and women inhabited different spheres appropriate for their sexes. As “new women” – women with college degrees and ambitions – began to have careers, their domestic sphere of influence expanded, but only so far. Jobs that involved promoting culture, social welfare, and the care of children – education, nursing, social work, and librarianship – offered women the opportunity to do paid work in public venues without violating the boundaries of the male sphere. Yet it gave women meaningful roles in shaping society, sometimes in subversive ways.

In addition to offering culture to the people, many libraries began to embrace a progressive impulse to bring opportunities to poor and working class citizens, offering a variety of social and cultural programs. These functions of public libraries developed in parallel to the Settlement Movement, also led by women, shifting the emphasis of some libraries from cultural uplift to becoming neighborhood-based social centers. This was also a function of the WPA library programs during the Great Depression, which built over 200 libraries and funded programs where there were no libraries.

There’s an enduring tension here in what libraries are: a traditional preserve for culture and learning, or a place where social issues are acknowledged and, in some small, local ways, solutions offered and tested. Today, as always, we find ourselves justifying our existence in diametrically opposed ways: providing practical value, such as preparing a workforce, supporting business development, helping students graduate on time, or saving households money, and the aspiration to improve society by providing a place to discuss civic issues, ensuring our community spaces are welcoming to all, and promoting the flourishing of a healthy, pluralistic, democratic society.

Let’s focus on a couple more of these core values: education and democracy. Right now, there is an enormous need for information literacy across all ages, and for a version of it that addresses the fact that we don’t always consciously seek information, it increasingly seeks us. We encounter volumes of information through a variety of channels that are shaped by commercial interests and are, in turn, shaped by people who want to influence how we see the world.

Currently, we’re all in a tizzy about ChatGPT and other generative AI systems that have scraped the internet and remix it based on statistical predictions, inventing likely answers rather than finding truth. We’re living through yet another tech hype cycle, knowing change is afoot but without any guideposts about what to expect. And, as usual, the tech industry is moving fast, not sure what it will break next.

Back in 2019, I participated in a Project Information Literacy research team that extended what we had learned about how college students process information and asked what they knew and felt about the algorithms that were increasingly shaping our information environment. We started by taking stock: what did it mean to live in “the age of algorithms”? These were some of the trends we identified:

- Data is no longer simply collected when we open a browser; we carry computers in our pockets that collect and share information about our daily lives. Enormous amounts of information are also being collected from our cars and household gadgets and health monitors.

- Advances in computation mean that data can be gathered and processed in real time, moving faster than the speed of ethics.

- When it comes to information seeking, the disaggregation and personalized redistribution of information through search and social media platforms makes evaluation difficult. We don’t all see the same information when we search and it’s not obvious where it came from.

- Automated decision-making systems are being applied to social institutions and processes that are being used to determine all kinds of things: who gets a job or access to social services. The potential for discrimination is enormous. Of course, discrimination isn’t new, but now it’s being hidden inside a shiny black box, which makes it harder to confront.

- Artificial intelligence is trained on incomplete and biased data sets, which means it will learn and amplify bias. This has implications from teaching autonomous cars how to avoid hitting pedestrians to recommending a prison sentence based on data from a criminal justice system that has a history of racial disparities. This is happening without public accountability.

- In the last two decades we’ve entered a new phase of late capitalism: the rise of the “attention economy” which uses personal data to drive targeted advertising, including political persuasion.

- These corporations seem unable to anticipate or respond to unintended consequences, behaving according to deep roots in Silicon Valley culture, which combines a worship of capital and ahistorical technosolutionism that responds to unintended consequences with not much more than a public “oops!” and a lot of private lobbying.

- Decades of media consolidation, deregulation, and economic trends combined with the rise of social media platforms that are designed for persuasion but have no ethical duty of care, have contributed to engineered distrust of established knowledge traditions such as science, journalism, and scholarship.

All of which is why I feel the values our profession evolved over the years have something important to offer. Privacy matters, because freedom matters, and living in a surveillance state, whether it’s run by corporations or governments, makes us less free. The public good matters. Equality matters, which means we must be ready to expose injustice, including in information systems. We value free speech, but we also know that absolutist approaches to free speech silences some voices, so we have to be thoughtful about how to balance those values responsibly. These are tasks that should be demanded of Google and Facebook and all of the technology companies that so thoroughly dominate our information landscape. Yet, most people feel powerless in the face of vast corporate resources doing things we don’t quite understand.

Libraries never quite live up to their values, but in the abstract libraries are ideally self-governing spaces belonging to diverse communities of neighbors. Libraries are civic spaces built and maintained as common ground for the public good. Imagine if the internet worked that way!

Understanding that the internet is not that way, and what that means for the flow of information, needs to be part of our information literacy efforts in all kinds of libraries. I found myself frustrated, in my years teaching information literacy in an academic library, that most of the time I was teaching students how to do school, not how information works in the world. Students did need practical help navigating the library, and they were naturally focused on completing the assignments they were given, but as an institution of higher learning, we weren’t doing much to explore the current information environment.

In the algorithm study, we heard that students didn’t expect to learn about the world of information at school. School was for … school, and they didn’t think their instructors understood it. When we interviewed instructors, we learned they were right: Their professors were very concerned about the state of our information environment, and hoped somebody would teach students about it; just not them, since it wasn’t their field.

It was discouraging to hear students say they really didn’t learn anything except how to use libraries for school assignments and didn’t expect to after I spent three decades promoting information literacy as if it matters for lifelong learning, not just student success. In spite of our efforts, students don’t seem to expect to learn about how information actually works, not when they’re in a classroom, but at the same time, they’re worried about their younger siblings and grandparents, who they feel are even more at sea. What was intriguing in our focus groups with students, though, was that they initially expressed frustration that their privacy was being routinely invaded, but felt there was little they could do. It was a tradeoff: their privacy for the use of tools they needed. But the more we discussed the bigger picture, the ways data was being gathered and used in automated decision-making, affecting people’s lives in significant ways, they seemed to grasp that this is a social issue, not just a personal one. It seemed to awaken in them a sense of agency, a belief that resistance wasn’t futile.

What I’m arguing is that, to really tackle information literacy, we need to address the world we live in and help people – not just students, everyone – learn about information systems: the architectures, infrastructures, and fundamental belief systems that shape our information environment, including the fact that these systems are social, influenced by the biases and assumptions of the humans who create and use them.

We need to emphasize not what to trust so much as why to trust, that ethical moves are involved in every exchange of information, and some of those moves have been institutionalized in useful ways. Trust in institutions of all kinds is so low these days. One reason is that distrust is cultivated for political reasons. We have a divided news and media landscape. Our news environment has been bifurcating since lobbying ended the Fairness Doctrine and aided the rise of right-wing talk radio and Fox news network, which is a self-referential system that places less value on journalistic fact-checking that on alignment with a set of values and beliefs.

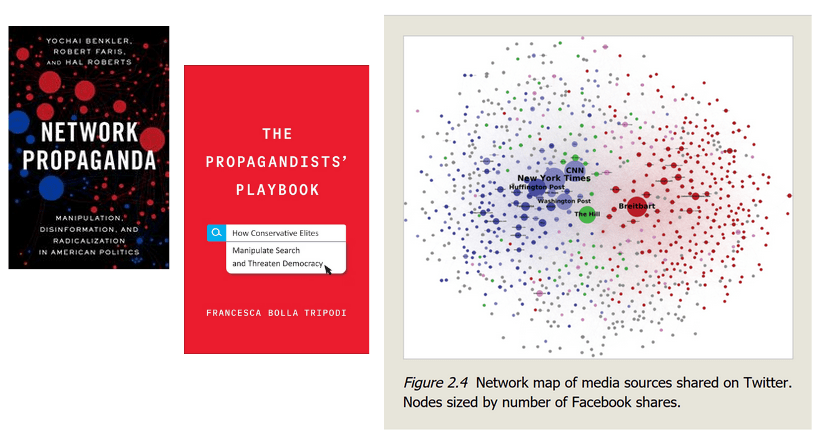

Network Propaganda is a 2018 study that looked at how supporters of Clinton and Trump shared news between 2015 and 2017; Francesca Tripodi’s more recent ethnographic study, The Propagandist’s Playbook, confirms its findings. This system is highly networked: A particular claim created in the far-right fringes gets taken up by political influencers, who then are invited to Fox News; those claims are amplified by politicians, and they are eventually covered by the mainstream press striving for “both sides” coverage, lending it legitimacy. In the mean time, leaders of this info-sphere tell its audiences that the mainstream press (and science, and education, and scholarly research, and the government) cannot be trusted. Rather, adherents are encouraged to go to Google to “do the research” themselves, but since political media activists have already seeded the internet with keywords and phrases that will show up in a Google search, that’s what will turn up in the “research.”

False claims made on the far-left fringes fail to gain as much traction because the left’s news consumers who may be susceptible to those claims value mainstream news sources and traditional journalistic practices – fact-checking, confirmation, issuing corrections when warranted. Manufactured misinformation can’t get as much traction.

Coupled with this difference in how we seek truth and evaluate claims, we have a tech industry that doesn’t particularly care about truth. Search is taken to mean shopping for the facts you prefer, with all the options available.

Added to that is the new convenience of a chatbot that can distill information online into a human-like conversation. It’s so eager to please, if it can’t find facts in its vast store of statistically-analyzed data, it will fill in the gaps with a simulacrum of truth. Recently a lawyer asked ChatGPT to draft a legal document. It wrote a highly persuasive court filing, but because there was no precedent that would support the case, it helpfully made some up. Though they are weirdly impressive, these large language models don’t understand the meaning of words, they merely arrange them in a sequence that is statistically probable. Whenever your main goal is profit, truth becomes a distraction, and that’s true whether you’re writing code, reporting a story, or conducting a scientific experiment.

The difference is some of these things have traditional guardrails built into their cultures and practices. When those guardrails are distrusted and everything that touches them is dismissed, the only tools left are built by companies whose purpose is creating shareholder value, not seeking truth.

This divide in our media systems is perplexing for librarians. We need to help people reflect on how they make decisions about information, and understand how the processes and practices of institutions like journalism and science, while hardly fool-proof, steer practitioners away from self-interested motives and provide ethical means of gathering and evaluating evidence. We don’t need to hand people the truth, we need to help them practice the art of what John Bushman has called “informational discernment.” As he puts it, “democracy doesn’t require a space cleared of distorting claims but spaces suited to grappling with them.” It’s not that all information is equally valid, but making meaning out of information is messy and complicated. We don’t have the answers, but we can help people frame good questions, evaluate evidence, and arrive at meaning for themselves while defending our spaces from organized bullies who want to limit what questions can even be asked.

It may well be that making information literacy opportunities that address these systemic issues won’t work for those people who are wholly committed to a limited number of sources they trust – like Fox and friends, or talk radio. But there are plenty of people in the middle who would be open to learning more about how information is created and what happens to it as it flows through our contemporary information infrastructures, and how it’s influenced by interested parties and commercial middlemen who care less about truth than about attention and virality. Unpacking how information works today need not be divisively political.

Coupled with this kind of media and information literacy, we need opportunities for people to learn from one another, get personal experience in bridging differences, and gain the confidence to believe they have the right to challenge systems that aren’t serving us well. As librarians, we need to do this ourselves, by learning about the issues, articulating our values, working in solidarity, and standing up for the importance of seeking truth ethically and with a critical understanding of the systems we use to do so.

During this second Gilded Age, libraries of all kinds must become places where all of these skills can be practiced as education for democracy. Given our long history of negotiating our fundamental values, we have more experience than big tech does helping people grapple with these big questions while also providing the public civic spaces where people feel they can belong, together.

Things I drew on . . .

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the new Jim code.Polity.

Buschman, J. (2003). Dismantling the public sphere: Situating and sustaining librarianship in the age of the new public philosophy. Libraries Unlimited.

Buschman, J. (2019). Good news, bad news, and fake news : Going beyond political literacy to democracy and libraries. Journal of Documentation, 75(1), 213–228.

Franks, M. A. (2019). The cult of the constitution. Stanford University Press.

Gerrig, R. J. (1993). Experiencing narrative worlds: On the psychological activities of reading. Yale University Press.

Head, A. J., Fister, B., & MacMillan, M. (2020). Information literacy in the age of algorithms: Student experiences with news and information, and the need for change. Project Information Literacy.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Ross, C. S., McKechnie, L., & Rothbauer, P. M. (2006). Reading matters: What the research reveals about reading, libraries, and community. Libraries Unlimited.

Wiegand, W. A. (2015). Part of our lives: A people’s history of the American public library. Oxford University Press.

Tripodi, F. B. (2022). The Propagandists’ Playbook: How Conservative Elites Manipulate Search and Threaten Democracy. Yale University Press.

Thank you for your blog post and ongoing efforts to counter false information. If not already encountered, your readers might be interested in the comments of Maria Ressa (winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace, partly for her ongoing fight against totalitarian propagandists). For example, she urges organizing a distribution system for facts a year ahead when a nation has elections coming up.

Also, a relatively recent article from researchers in UK and Ireland on “Countering Misinformation” that evaluates evidence on some ways to tackle false, public information is reviewed in my recent blog post at: https://communicator.rodney-miller.com/2023/07/countering-misinformation.html

Cheers, Rod

Hi Barbara, I wanted to let you know that the women’s prison history book that you helped with has been published. I’m not sure if I have the right email for you so am posting this message here. Kelsey

How exciting! Thanks for letting me know. What a fabulous project.