Fear provides the momentum of much crime fiction – giving the reader the benefit of an adrenaline rush without any actual risk. We must enjoy being anxious; otherwise the bestseller lists wouldn’t be so dominated by thrillers. Patrick Anderson suggests the genre is not only entertaining, it satisfies an urge to examine the darker parts of society without entirely sacrificing hope. Yet, according to critic Stephen Knight, we can no longer assume that in a fictional framework wrongs will be righted, that order will be restored. Instead, the representation of violence and social injustice in crime fiction today “provides a coherent form of contemporary anxiety” and gives our deepest fears narrative shape.

Fear also plays a political role. Inchoate fears can be heightened and focused on an invisible enemy in order to discourage dissent. When doing background reading for In the Wind, I was surprised to see how little editorial work it would take to turn the 1976 Church Committee report on the abuses of government surveillance during the Vietnam War era into a description of today’s climate for civil liberties. Just replace the variations of the word “Communism” with “terrorism.” Plus ça change.

I was raised in the 1960s in Madison, Wisconsin, a pleasant university town between two enormous lakes, where resistance to an unpopular war led to frequent street battles. Though mass protests aren’t so frequent these days, I’ve had a near-constant sense of déjà vu during our current state of war. As I write this, I’ve just read a story in this morning’s New York Times that details the recently-declassified plans that J. Edgar Hoover drew up to suspend habeas corpus and arrest and detain 12,000 people who he considered “disloyal” just weeks after the start of the Korean War. It’s eerily similar to the way that, just weeks after 9/11, the president issued an order that allowed the government to detain people indefinitely without charges and without access to lawyers; Congress eventually followed suit by legalizing the denial of habeas corpus to those considered “enemy combatants.”

As the Times reports on a historical plan to suspend civil liberties, the Washington Post describes the FBI’s current efforts to build an enormous database of individual’s characteristics. If all goes as planned, biometric data – a scan of a pupil, a scrap of DNA, or an image of a face – can be matched like fingerprints, with data shared across agencies or with corporations doing background checks. The public imagination has grown attached to technological wizardry that seems to give us such scientific certainty. Unfortunately, the only large-scale study of such biometric tracking systems suggests they lead to a large number of false positives. It’s not hard to imagine being erroneously caught up in a nightmare scenario as J. Edgar’s handpicked list expands into the millions and becomes automated and ubiquitous.

It is in those strangely parallel universes, that of the Nixon era and post 9/11 America, where I set In the Wind. I got the first teasing itch of a storyline several years ago when a Minnesota woman who lived a quiet middle-class life was arrested by the FBI. They claimed she had been a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, one of the stranger radical groups that arose out of the conflict of the sixties. I wondered what it was like for someone to live underground for so many years, and how it affected her family and friends to learn she had an alternate identity and a radical political past.

Even earlier, I felt an urge to write about the reality of mental illness. Crime fiction quite often exploits false stereotypes about mental illness to provide its monsters. It’s easier to be entertained by evil that is safely distanced from us. We can explore the dark side without risking being implicated in evil committed by people who are fundamentally different than us. Yet in fact, people with a mental illness are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators – and they are not different. The National Alliance for the Mentally Ill estimates that one in 17 Americans suffers from a major mental illness; twenty percent of families in the US are affected. Yet, because of social stigma, we don’t generally talk about it, so the mentally ill remain fair game for demonization. For me, the issue is personal. My brother Paul, my best friend in childhood, was misdiagnosed as schizophrenic while in college; in fact, he had a form of bipolar disorder that included powerful delusions during manic phases. He struggled with the illness until his death, and so did we, because so often in a crisis there was absolutely nothing anyone could do to help. One in five families goes through the same thing.

So in this book, I tried to braid together a family’s all-too-common personal crisis as they deal with a child with bipolar disorder, with national events, then and now. In the story, a Native American activist wanted for the murder of an FBI agent in 1972 is hunted in the present time, using methods reminiscent of the counterintelligence activities that were exposed as unconstitutional after Watergate. Past collides with present, and the political becomes personal.

Part of me hoped this strange resonance between then and now would be passé before In the Wind was published. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case. Earlier this month, a senator from Connecticut said these words on the floor of the US Congress:

Americans have rightfully been concerned since before World War II about the dangers of hostile foreign agents likely to commit acts of espionage. Similarly, the violent acts of political terrorists can seriously endanger the rights of Americans. Carefully focused intelligence investigations can help prevent such acts.

But too often intelligence has lost this focus and domestic intelligence activities have invaded individual privacy and violated the rights of lawful assembly and political expression. . . . intelligence activity in the past decades has, all too often, exceeded the restraints on the exercise of governmental power which are imposed by our country’s Constitution, laws, and traditions.

We have seen segments of our Government, in their attitudes and action, adopt tactics unworthy of a democracy, and occasionally reminiscent of the tactics of totalitarian regimes. We have seen a consistent pattern in which programs initiated with limited goals, such as preventing criminal violence or identifying foreign spies, were expanded to what witnesses characterized as “vacuum cleaners,” sweeping in information about lawful activities of American citizens.

That these abuses have adversely affected the constitutional rights of particular Americans is beyond question. But we believe the harm extends far beyond the citizens directly affected.

Personal privacy is protected because it is essential to liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Our Constitution checks the power of Government for the purpose of protecting the rights of individuals, in order that all our citizens may live in a free and decent society. Unlike totalitarian states, we do not believe that any government has a monopoly on truth.

When Government infringes those rights instead of nurturing and protecting them, the injury spreads far beyond the particular citizens targeted to untold number of other Americans who may be intimidated. . . . Secrecy should no longer be allowed to shield the existence of constitutional, legal and moral problems from the scrutiny of all three branches of government or from the American people themselves.

He was reading the words of Frank Church, first spoken in the 1970s. And they were never more true.

December 2007

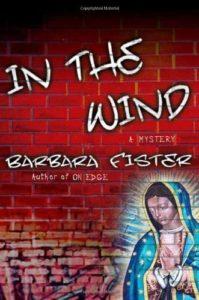

These photos were taken in Chicago back in 2007.

Header photo by Jonas Bengtsson.