I got to give a talk at ER&L about Project Information Literacy‘s latest study. Here’s the text.

I got to give a talk at ER&L about Project Information Literacy‘s latest study. Here’s the text.

Libraries and the Practice of Freedom in the Age of Algorithm

Abstract: How prepared are librarians, and the students they serve, to navigate technologies that are fundamentally changing how we encounter, evaluate, and create information? In the past decade, a handful of platforms have become powerful information intermediaries that help us search and connect but also are tools to foment disinformation, amplify hate, increase polarization, and compile details of our lives as raw material for persuasion and control. We no longer have to seek information; it seeks us. Project Information Literacy has revealed college students’ lived experience through a series of large-scale research studies. To cap a decade of findings, we conducted a qualitative study that asked students, and faculty who teach them, what they know and how they learn about our current information environment. This talk explores what students have taught us, where education falls short, why it matters, and how time-tested library values – privacy, equity, social responsibility, and education for democracy – can provide a blueprint for creating a socio-technical infrastructure that is more just and equitable in the age of algorithms.

I’m going to start with a confession. I lived in Austin for a number of years, and never once considered that I occupied land that rightly belonged to others. This place was inhabited by Tonkawa people before forced removal. Other indigenous peoples had lived on this land for some 11,000 years. Since moving to Minnesota I’ve become more aware of the fact the land I’ve lived on for over thirty years is the unceded territory of the Dakota people of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ.

It was taken from them in a deceptive treaty signed the same year that the college I worked at was founded by newly-arrived Swedish immigrants. The Dakota people didn’t simply vanish when the treaty wasn’t honored and starvation loomed. They resisted. Ten miles or so south of my home and the library where I spent most of my career is the site of the largest mass execution in US history, held the day after Christmas in 1862. Every year, native people gather at that site in remembrance. They are still here, they still face discrimination and exploitation, they fight to heal the earth, and I acknowledge that I live on land that rightfully belongs to them.

It was taken from them in a deceptive treaty signed the same year that the college I worked at was founded by newly-arrived Swedish immigrants. The Dakota people didn’t simply vanish when the treaty wasn’t honored and starvation loomed. They resisted. Ten miles or so south of my home and the library where I spent most of my career is the site of the largest mass execution in US history, held the day after Christmas in 1862. Every year, native people gather at that site in remembrance. They are still here, they still face discrimination and exploitation, they fight to heal the earth, and I acknowledge that I live on land that rightfully belongs to them.

I wanted to say this because we must do what we can to make amends to those who are still here, resilient in the face of continuing displacement and generational trauma, still here, teaching us our true history. But today I want to talk about a different kind of injustice, something that isn’t as brutal as the genocide of native peoples, but which has some parallels with colonization. You could call it massive legalized identity theft, or you could call it everyday life in the age of algorithms. Or you could use the phrase Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejia use in their book, The Costs of Connection: “data colonization.”

Classic colonialism involved a number of moves: appropriating others’ land and resources, creating unequal relationships to enable subjugation and enslavement, ensuring the colonizers reaped the greatest benefits, while developing an ideology that could excuse it all as the advance of civilization. The title of this rather scary propaganda painting is “American Progress.”

Today’s data colonialism is different, but makes some of the same moves. It assumes data about us, the cloud of data that is shed like skin cells as we move about our days, is a supply raw material just lying there, ready to be appropriated. It enshrouds how that appropriation works in trade secrecy while exposing intimate details of our lives and relationships, creating an unequal relationship. The benefits of that appropriation of data are huge. You know the old saw, “data is the new oil?” In the past ten years, the companies that collect the most data have displaced Big Oil on the list of the world’s largest companies by market capitalization. The biggest data collectors are not only the new oil barons, they are practically new nation-states. And finally, their ideology, their civilizing mission, is based on a form of libertarian hyper-capitalism framed by white male belief in meritocracy, a global reach matched only by cultural incompetence, and magical thinking about the preeminent goodness of individualism and free speech – masked by happy blather about how everything they do inevitably makes the world a better place.

What does it mean for librarians? As information professionals we need to learn as much as we can about this extraordinary shift in our information environment because it’s happening fast and its breaking a lot of things. We need to think about how our professional values map to or are thwarted by data colonialism, and we need to think about how we can contribute to making change. Those of you in the ER&L community are particularly well aware of how technology shapes libraries and influences how users relate to information. We need to think about how to help our students and faculty understand what’s going on in the world of information. About what’s happening to what we think we know. About what’s being taken from all of us – the fine-grained details of our lives and relationships, all in the hopes of influencing our future behavior.

What does it mean for librarians? As information professionals we need to learn as much as we can about this extraordinary shift in our information environment because it’s happening fast and its breaking a lot of things. We need to think about how our professional values map to or are thwarted by data colonialism, and we need to think about how we can contribute to making change. Those of you in the ER&L community are particularly well aware of how technology shapes libraries and influences how users relate to information. We need to think about how to help our students and faculty understand what’s going on in the world of information. About what’s happening to what we think we know. About what’s being taken from all of us – the fine-grained details of our lives and relationships, all in the hopes of influencing our future behavior.

This need to educate our communities about what is happening right now is what drove the latest research project undertaken by Project Information Literacy. I was thrilled to be invited to spend a year as a “scholar in residence” with a research institute that I had admired for a decade. It was great because I’ve been fangirling all over the place for as long as the project has been in existence and this opportunity let me work with a great research team to look into what it means to be information literate at this point in time.

For background, PIL is a non-profit research institute directed by Alison Head and it has conducted the most complete body of research on how college students navigate information – on how they manage when they arrive at college, how they find and evaluate information for school and personal life, what happens after they graduate, and most recently how they engage with news. It has used both qualitative and quantitative research methods to probe the student’s lived experience at colleges of all kinds across the country. So far, it has involved 22,000 students attending 92 institutions in producing this research, all of which is open access.

(I should pause here to thank ER&L for helping to fund this study, along with the Knight Foundation, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, the University of South Carolina School of Library and Information Science, and individual donors who helped to fund travel to field sites and other expenses. We’re deeply grateful.)

This project set out to address three questions:

- What is going on with information these days? What does it mean to live in an age of algorithms, and how does that inform what we know about how college students currently learn about and interact with information?

- How aware are students of the ways algorithms influence the news and information they encounter daily, and are they concerned about the ways algorithmic systems may influence us, divide us, and deepen inequalities?

- What should we do to help students become information literate – not just to complete college assignments but to live in a world where information is increasingly mediated by algorithmic systems that affect our lives while being largely unaccountable black boxes?

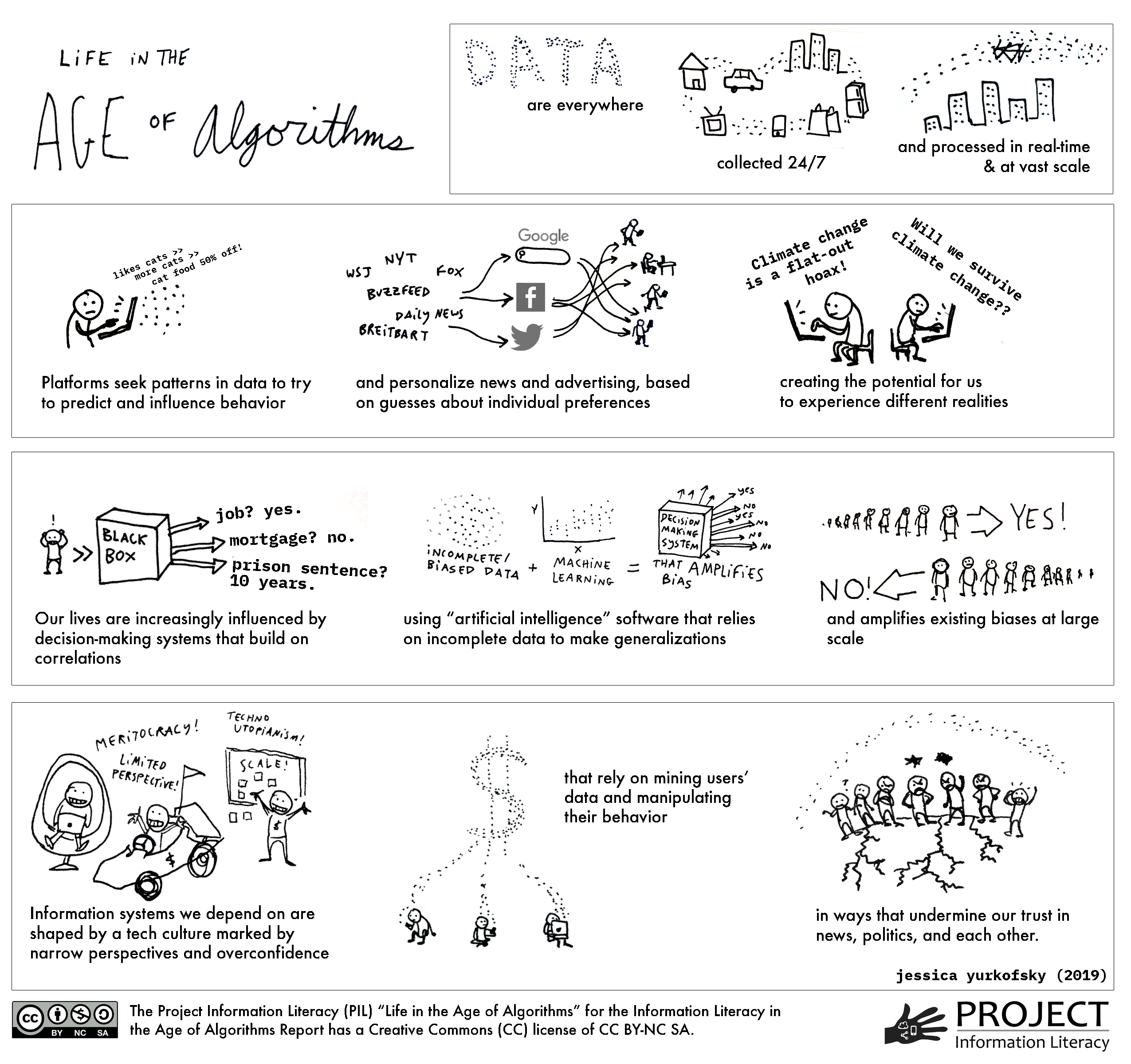

We started by taking stock: what did we actually mean by “the age of algorithms”? To make sure the entire research team was on the same page, I digested some trends to create a backgrounder for the team – and our gifted research fellow, Jessica Yurkovsky, summarized the points in a terrific graphic that’s available for reuse at the PIL website.

Here are some of the key trends we identified:

- Data is no longer simply collected when we open a browser; we carry computers in our pockets that collect and share information about our daily lives, including where we go, who we associate with, and what questions we ask. Enormous amounts of information are also being collected from our cars and household gadgets and health monitors.

- Advances in computation mean that data can be gathered and processed in real time. This computational ability to quickly manipulate enormous amounts of fine-grained, exhaustive data collected from multiple sources is new and big – and moving faster than the speed of ethics.

- When it comes to information seeking, the disaggregation and redistribution of information through search and social media platforms makes evaluation of what used to be distinct sources, like articles published in a particular journal or stories in a local newspaper, all the more difficult. It also personalizes results based on inferences drawn from personal data trails. We don’t all see the same information when we search and it’s not obvious where it came from.

- Automated decision-making systems are being applied to social institutions and processes that are being used to determine all kinds of things: who gets a job or access to social services. Our students are likely to be interviewed through a system that alleges it will sort good job candidates from bad based on hype and pseudoscience – and the potential for discrimination is enormous. Of course, we already see discrimination in hiring, but now it’s being hidden inside a shiny black box, which makes it harder to confront.

- Artificial intelligence is “trained” using incomplete and often biased data sets, which means it can learn and amplify bias. This has implications from teaching autonomous cars how to avoid hitting pedestrians to recommending a prison sentence based on data from a criminal justice system that has a history of racial disparities.

- We’ve entered a new phase of late capitalism: the rise of the “attention economy” or “surveillance capitalism”— a profitable industry based on scooping up “data exhaust” to personalize, predict and drive behavior, tailoring to a fine degree advertising, political persuasion, and social behavior. Political persuasion has entered a whole new realm.

- These corporations seem unable to anticipate or respond to unintended consequences, behaving according to deep roots in Silicon Valley culture, which combines the capitalist excesses of the Wolf of Wall Street “greed is good” days with “technology is good” techno-solutionism that responds to unintended consequences with not much more than a public “oops!” and a lot of private lobbying to keep “great power” and “great responsibility as far apart as possible.

- Decades of media consolidation, deregulation, and economic trends combined with the rise of social media platforms that are designed for persuasion but have no ethical duty of care, have contributed to engineered distrust of established knowledge traditions such as science, journalism, and scholarship.

All of which is why I feel the values our profession evolved over the years have something important to offer. Privacy matters, because freedom matters, and living in a surveillance state, whether it’s run by corporations or governments, makes us less free. The public good matters. Equality matters, which means we must be anti-racist and critically aware of and ready to expose injustice. We value free speech, but we also care about social responsibility, and know that absolutist approaches to free speech silences some voices, so we have to be thoughtful about how to balance those values responsibly.

These core values have been developing over decades, and we’re still working out how to put them into practice, but aren’t these the very questions we must be asking of Google and Facebook and all of the technology companies that so thoroughly dominate our information landscape today? You are the librarians who can provide us all with leadership and insights, because you deal daily with technologies and competing interests and have your finger on the pulse of what’s happening and what’s possible. You can guide us as a profession as we develop an understanding of technology’s effect on society.

So, let me bring this back to the work we do with our students. We wanted to bring together what we’ve learned about students so we could take the next step.

Students have trouble getting started, because we so often ask them to develop a thesis about subjects that are new to them. They develop shortcuts, because they are busy and anxious and can’t afford to take intellectual risks. Evaluating sources is a social process – but only a minority of students include librarians in that social sphere. After they graduate they tend to believe their education gave them some useful skills when it comes to information seeking and critical analysis, but they didn’t think they learned how to ask questions of their own – which blows my mind, because being able to ask good questions should be basic preparation for lifelong learning, personal growth, and meaningful civic engagement. In the 2018 news study we learned a slight majority of students aren’t confident they can tell good reporting from BS, and fully a third don’t trust any news at all.

Following the news study, it seemed the right time to step back and look at the broader information landscape beyond school, beyond the workplace, beyond journalism itself, and think about this rapidly changing technical infrastructure that depends on big data, algorithmic computation, and statistical models that work on assumptions that are hidden from us.

We selected eight institutions that were as representative as we could manage of student demographics, types of institutions from community colleges to research universities, and political geographies – choosing field sites in rural and urban locations, in red and blue states. At those institutions we conducted two in-person focus groups involving a total of 103 students. We also conducted phone interviews with 37 faculty teaching at those institutions. We transcribed these conversations and the team went through them to see patterns, followed by a more formal coding process. We sorted out four major takeaways from what we heard from students.

College students feel two contradictory emotions about algorithm-driven platforms: indignation and resignation. Students are very aware of the workings of algorithms that track their interactions. They mostly see these in advertising – which many described as “creepy” as ads followed them across devices and platforms. They also feel they have no choice but to use these systems, and no way to influence the companies that track them. As one student put it,

It’s a horrible, totalitarian hellscape, but it’s kind of the best we can reasonably expect.

Students do take action on a personal level: many use defensive practices to protect their privacy. Many learned privacy protection strategies, such as using ad blockers and VPNS, from peers, not in the classroom. They were really interested in learning more – in fact, during the focus groups, students would begin to take notes on what they were learning from one another. The faculty we interviewed seemed far less knowledgeable about privacy strategies. One student drew out a deeper concern about the implications for society, saying

I’m more concerned about the larger scale trend of pushing what we want, but also predicting what we want in ways that push a lot of people towards toward cultural and political hegemony.

She added, “I feel like that’s talked about less than, like, individual privacy aspects.”

Skepticism dominates; trust is much harder to come by. Students who noted they grew up with the internet and came of age with smartphones and social media accounts, had a certain level of cynicism about the reliability all information. They were schooled to be skeptical, told by parents and teachers the internet was a dangerous place and every source was dubious had to be scrutinized. As one put it,

Between, like, students and professors, I think how we’re accustomed to taking in information is different because they come from like a pre-social media age and they’re used to being able to trust different resources that they’ve always gone to. Whereas we grew up with untrustworthy sources and it’s grilled into us you need to do the research because it can’t be trusted.”

This observation was borne out in faculty interviews. Most faculty reported they relied on a set of trusted news sources to keep up, but students got news through multiple social channels, online and through face to face relationships. They were less likely to name specific trusted sources. Trust is as important as skepticism. Trust in science, in expertise, in good journalism – it saves you from feeling you have to develop expertise yourself. More problematically, “research it yourself” is something conspiracy theorists emphasize. How do you discover the earth is flat or the government is run by lizard people? Do the research. The marketplace of ideas has expanded – it’s a real buyers’ market these days, especially on platforms that are built for persuasion and engagement, not for subtlety or nuance.

Discussions of algorithms rarely make it into the classroom. This to me was the most mind-blowing discovery of all, yet I don’t know why I was so surprised. In interviews, most faculty expressed deep concern about algorithms used by influential for-profit companies that mediate information in a polarized political environment. But very few addressed this concern in their courses. Some seemed a bit stunned to realize they had never considered it; others thought it would be a good idea – so long as someone else taught it. Students didn’t expect to learn anything useful about information in their courses. As one student summed it up,

Usually it’s like a two-day thing about ‘this is how you make sure your sources are credible.’ Well, I heard that in high school, and that information is kind of outdated. I mean, it’s just not the same as it used to be.

They were more worried about the younger generation, whose lives have been broadcast from birth on social media. But as conversation continued, students began to make connections to broader social issues. For example, one student said of decision-making algorithms

It’s just a fancy form of technology for stereotyping and discrimination that’s inherently problematic because we can’t see it.

Through our conversations, something began to grow in that space between resignation and indignation, and that’s where some fruitful learning could happen: Learning that isn’t just finding the kind of sources that will make professors happy. Learning that might develop a better ability to ask hard questions, to own the right to demand change, to connect social justice to the things being done to us. To practice freedom.

So, where do we go from here? It’s a daunting task, given the limits we already confront in helping students learn how information works, but we came up with some recommendations, ones that I hope can give people ideas they can implement locally, on a small scale, using whatever limited resources are available.

So, where do we go from here? It’s a daunting task, given the limits we already confront in helping students learn how information works, but we came up with some recommendations, ones that I hope can give people ideas they can implement locally, on a small scale, using whatever limited resources are available.

Encourage peer-to-peer learning to nurture personal agency and advance campus-wide learning. We found students were eager to learn about technology, deeply interested in the big problems underlying systems they use every day, very interested in learning more about how these systems are being used in society, but they felt their instructors weren’t up to speed, that this kind of information literacy had nothing to do with their courses. This opens up the potential for involving students as co-designers of learning experiences. For example, a skill-share session could be organized on campus with stakeholders from student affairs, academic departments, IT, and the library in which students lead conversations about the social implications of data-driven decision systems and provide hands-on training on tools and strategies, such as surveillance self-defense. Students could also be engaged in discussions of technology adoption on campus, investigating the data-collecting practices of systems used by the institution to promote campus-wide discussion about data privacy. Seeing the way students learned defensive practices from one another suggests is an opportunity to break down the authority structures that inhibit students from owning their own education. The library, as common ground for the campus, would be a good host for kicking off such a program.

The student experience must be interdisciplinary, holistic, and integrated K-20. This one is tougher to tackle. Students in our focus groups described their exposure to information literacy and critical thinking from elementary school through college as scattered, inadequate, and disconnected. We need to do more to make information literacy instruction – or digital literacy, or media literacy, whatever you want to call it – coherent and holistic, which will require the formation of alliances across disciplines and education levels to better coordinate and update information literacy and critical thinking instruction. Local efforts could start with finding stakeholders on college campuses who have already built bridges to the local schools and into the community. These may be teacher education faculty, coordinators of programs that pair college students with elementary school students, community outreach programs and student participants. Working through existing connections, educators, students, librarians from public, school, and academic sectors could be invited to an open-ended discussion and workshop. Such a gathering could audit what students are learning, map connections across the learning experience, identify gaps, and seek ways to continue working together. Admittedly this is hard work, given the different cultures of K12 teaching and higher ed and the dearth of incentives to collaborate but maybe there are some good things that could come from starting small with a grassroots effort to connect and share. The good news is that a lot of people care about this kind of learning, and we can nurture that interest and build bridges across educational levels – bridges we expect our students to cross routinely.

Learning about algorithmic justice supports education for democracy. Despite their aura of sophisticated cynicism, students in our focus groups became energized when discussing the impact of algorithms on society. Opportunities to introduce learning about algorithmic justice can be found throughout the curriculum and in programs that link higher education to the broader community. Every day new issues surface: given its high error rate, should we ban facial recognition? When police departments promote Amazon’s Ring doorbell to develop neighborhood surveillance networks, who gets hurt? Is it okay for Google to get patient data from hospitals to develop AI-enhanced diagnostics? What should Congress do to rein in the capacity for big tech to claim our data? It is around topics like these that students can break out of a sense of helplessness, be emboldened with personal agency to grapple with complex issues, and feel empowered to take on the challenge of promoting algorithmic justice. At a practical level, individual instructors can look out for stories in the news that link their subject matter to issues of algorithmic justice: How does the digital surveillance of children influence child development? What information could help hospitals follow up with patients without introducing bias? How does microtargeting ads for jobs and housing relate to the history of redlining? Librarians who serve as liaisons to academic departments could support these efforts by creating ongoing curated collections of relevant news stories targeted to specific courses and disciplines, strengthening their own algorithmic literacy while broadening the working definition of information literacy on campus. By injecting current controversies around the algorithmic systems that influence our lives into their course material, educators can tie their disciplinary knowledge to pressing questions of ethics, fairness, and social justice – questions that our students are deeply invested in.

This is the kind of learning libraries exist for. We’re not here just to help students be students, not just to teach them how to find and use a certain kind of information to accomplish tasks required for school but unrelated to life after college. Ideally, our work will help students understand where information comes from, how it’s connected to social processes, how they themselves can participate in those processes ethically, and how they can bring their critical understanding and concern to bear on making those processes more just. Ideally, the ethical practices we promote in our libraries will model for students what information ethics means in the wider world. We want our students to have the audacity to believe they can overcome this manufactured polarization, this splintering of meaning into profitably agitated market segments, and instead feel equipped to pose problems, make meaning, and even – make things change.

Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed speaks to this:

Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

Right now, the logic of the present system is ubiquitous, running in the background, hidden in a black box, consuming intimate details of our lives to combine with other data sources to build an “architecture of persuasion.” The technical infrastructure that channels and shapes so much of our understanding and social interaction was created in the utopian belief that making information universally available and giving every individual a voice would improve our lives. But as that infrastructure became an engine of surveillance and persuasion, trading in the details of our lives to create sophisticated marketing tools to sell consumer goods and ideas, that utopian ideal has become dystopian. The power of machine learning and artificial intelligence has been unleashed without regulation or informed consent. It is no wonder both students and faculty in this study felt helpless and anxious about the future.

We are facing a global epistemological crisis. People no longer know what to believe or on what grounds we can determine what is true. As librarians, we know information doesn’t have to work this way. Our values could be a guide to healing the social fractures that technology has widened.

If we own this challenge, if we help our communities understand what’s going on in the world of information today, we will all be better prepared to tackle both the unchecked power of tech giants as well the social problems their algorithms exacerbate. This education for democracy — both formal and beyond — can engage our students in the practice of freedom and empower them to participate in transforming the world.

Image sources

- librarian bomber, adaptation of Bansky by hafuboti via Wikimedia Commons

- Photo of Dakota riders at the 38+2 memorial in 2012, photo by The Uptake

- John Gast, “American Progress,” 1872, via Wikimedia Commons

- World map based on internet census, 2012, via Wikimedia Commons

- Doris Rudd Porter, “human computer,” with Manometer tape, ca. 1946 (?) via NASA

2 thoughts on “libraries and the practice of freedom in the age of algorithms”