. . . but if it’s on the internet, who’s to say?

. . . but if it’s on the internet, who’s to say?

A few days ago, Forbes published a blog post by an economics professor that argued we should close public libraries because Amazon could fill that increasingly insignificant niche, which would help the economy and stop wasting taxes. It turned into a Twitter spectacle.

This happens now and then. Someone writes a piece saying “why do we even have libraries anymore? We have the internet,” or “Amazon,” or “who even reads books these days?” and the reaction is swift and scalding. In this case, reacting became a group sport: “I’m here for the ratio.” (I confess I wasn’t quite clear what that meant, but apparently if a tweet gets more comments than likes and retweets, it’s a sign that a lot of people found something stupid on the internet and more people should pile on.) Some folks referred to it obliquely but refused to link or add to the thousands of comments because it would be encouragement to publish similar stuff. It doesn’t matter whether it’s good or bad, it’s all about the clicks. The attention economy doesn’t do content discrimination.

In this case, though, apparently the attention became unwelcome and before long the post was replaced by a 4-0-Forbes error message (their riff on a standard html error message for a page that is no longer there). It wasn’t retracted or corrected, it just vanished. Forbes told Quartz “Libraries play an important role in society. This article was outside of this contributor’s specific area of expertise.” (Actually, he was making an economic argument that taxes should not fund things that compete with Starbucks as a place to hang out or Amazon as a place to buy books; it seemed completely within his expertise to speculate; he simply failed to develop a convincing argument.) At some point, no matter how many clicks you get, the wrong kind of attention can become a liability.

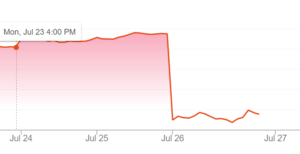

That may have played a small role in the dramatic Facebook stock sell-off this week. On Thursday, after a disappointing earnings report and a prediction that shareholders should expect slower growth, the stock fell by 20 percent, a one-day loss of $124 billion in value, the largest plunge for a single company’s stocks ever. It’s not totally surprising. After you already have 2 billion users, it’s hard to keep adding more at the same rate, especially without access to China. But Facebook is also struggling to find ways to stanch the flood of embarrassing news and create ways to make it a happier place that allows everyone to say what they want without enabling political division and violence.

In a Recode interview, Zuckerberg said Facebook had two core principles: giving people a voice and keeping people safe. Those don’t always play well together. Does giving holocaust deniers a platform make people unsafe? There’s an argument it does, both because it’s setting a seat at the table for violent antisemitism and it is a deliberate attempt to undermine our very belief in the existence of facts. As Johannes Breit argues, giving neo-Nazis a platform where they can open the Holocaust up for debate is an attempt to make Nazism socially acceptable. More broadly, it suggests nothing is true, and anything is possible. (This is also why it’s problematic that our president lies so often while telling us not to believe what we see or read, as explored in a recent New Hour segment. It’s corrosive to society.)

At the same time, in his interview, Zuckerberg said Facebook had to take responsibility for what Facebook does. He’s acknowledged the company’s tools can be used for harm, and it’s trying a variety of means of screening flagged content and giving counter-factual narratives less attention. The trouble is, Facebook and other platforms for user-generated content make money through attention. The ways attention has been manipulated on Facebook has threatened the reputation of the platform (not to mention democracy), but the very design of the platform is all about manipulating attention. Giving everyone a voice pays better when those voices are loud and making lurid claims.

Exposure to a range of ideas and opinions is good, but freedom to believe whatever you want needs to be tempered by some shared notion of how we determine things to be true or false. Otherwise, we’re not just saying it’s fine to yell “fire!” in a crowded theater that isn’t, in fact, on fire, we’re saying it’s fine to disable the smoke detectors.

reposted from Inside Higher Ed.