Minitex, our local library cooperative (consortium? collaboration?) is fifty years old, and I got to speak at a virtual party, where there were videos submitted by member libraries, some speakers, and a fun breakout Jeopardy game where I got a couple right but otherwise made a fool of myself. All in a good cause – cheers for fifty years! And cheers for a well-organized Zoom gathering. Here’s the text of what I said.

Minitex, our local library cooperative (consortium? collaboration?) is fifty years old, and I got to speak at a virtual party, where there were videos submitted by member libraries, some speakers, and a fun breakout Jeopardy game where I got a couple right but otherwise made a fool of myself. All in a good cause – cheers for fifty years! And cheers for a well-organized Zoom gathering. Here’s the text of what I said.

Fifty/Fifty: Drawing on the Past to Envision the Future of Minitex

I’m delighted to be part of this wonderful anniversary celebration. Like all of you, I’ve benefitted immeasurably from Minitex, both as a librarian and as a citizen. My relatively small college library couldn’t possibly afford to provide all the information our students and faculty want. Interlibrary loan is the most public-facing Minitex service our community enjoys, but we also benefit behind the scenes from cataloging training and development, cooperative purchasing of things like tattletape, licensing of databases, ELM (now eLibrary), and recently the Minnesota Library Publishing Project, which several of our faculty embraced for publishing local histories or creating class projects, and so on.

As a citizen, likewise – my small local public library would have a hard time keeping up with the appetites of avid readers like me without a system of sharing materials, and that’s on top of all the rest that Minitex does for the public and school libraries of the region.

Imagine a world without Minitex, without the cooperative spirit that animates it: it would be a poorer place. And chances are, we would be turning more and more to the for-profit sector to serve our communities.

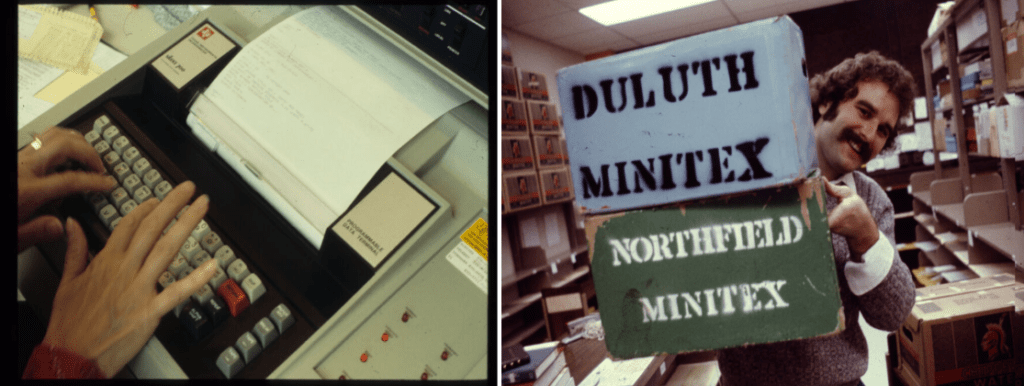

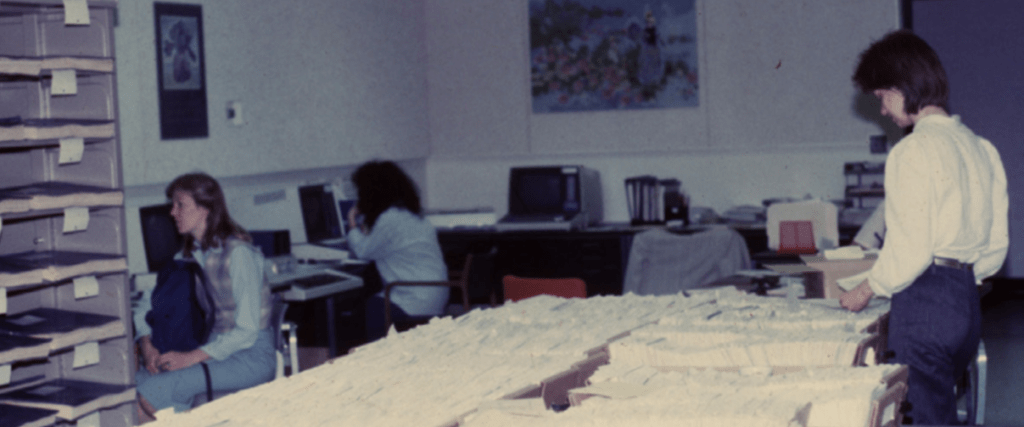

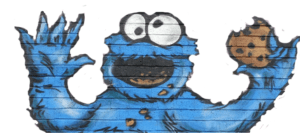

In a sense, Minitex’s history is the history of combining library values with technological tools and practical problem-solving to make all of our libraries stronger. Early on, teletype was the technology used for communicating among libraries. Books were loaded into crude wooden boxes and transported by Greyhound bus, a forerunner to the courier service.

A combined list of serials was created – remember MULS? Imagine how much work that was. Though it was a machine-readable file, I remembered it being a fat set of microfiche in a red binder.

It was cutting-edge, the first set of records entered into OCLC to kick off CONSER, the OCLC-based cooperative serials program. I just knew those microfiche were incredibly useful for finding out who might have that article one of our community members wanted. Getting this cooperative system off the ground involved creativity and a lot of hard work from a lot of library staff.

Since I was in public services, I didn’t do that work, but I definitely talked about interlibrary loan with faculty interviewing for positions – yes, actually, you can continue your research here at this small undergraduate library, we have Minitex to back us up. It was essential for students who wanted to do serious research without being at a research university, and it made a difference in terms of the curriculum that we could offer.

When I first taught students how to make interlibrary loan requests, they did it by filling out paper cards; we advised them that books and journal articles might take as much as ten days to arrive. Now you might get an article before the day is out, and I’m always astonished at how quickly books arrive. In fact, there was a period of time when much of our journal collection was still in print that students preferred discovering they had to rely on interlibrary loan – it saved them the trouble of hunting for the issue of the journal and paying ten cents a page to photocopy the pages themselves.

Now that most of the collection is online, the learning curve has taken a slightly different direction. They are confused by making the jump from a reference encountered on the open web to having the article in their hands. But  what a wonderful thing it is, when a student who looks crestfallen because the article they found online that looked perfect for their research – the one that has a $45 price tag on it – finds out it can be theirs at no charge and often in just a matter of hours. Or when they realize they can request a book they want to read simply for fun and it will be sent to their library. Miraculous.

what a wonderful thing it is, when a student who looks crestfallen because the article they found online that looked perfect for their research – the one that has a $45 price tag on it – finds out it can be theirs at no charge and often in just a matter of hours. Or when they realize they can request a book they want to read simply for fun and it will be sent to their library. Miraculous.

Of course, these miracles take a lot of hidden labor, and a lot of imagination. I often wonder, if we didn’t have Minitex today, could we imagine it into existence, or would we expect the private sector to figure it out. Maybe some tech innovator would invent the Netflix of library sharing. Would we have training for cataloging, or would we expect we’d have to hope somebody who actually knew what they were talking about had created a YouTube video? Would we think interlibrary sharing would depend an app like InstaCart or Deliveroo that would use gig workers to drive books from one library to another for a fee? I hope we would imagine something different, that we dust off our core library values and imagine together the radical idea of a library-to-library solution. A collaborative, cooperative solution. A solution like Minitex.

Many years ago I copied down a quote from Alice Wilcox, the first director of Minitex, that struck me powerfully. Trying to backtrack and find the source was challenging. It came from a 1984 symposium; a snippet had been reproduced somewhere – maybe the Minitex messenger? I had jotted it down because it seemed so prescient, but I couldn’t find the original. I finally wrote to Maggie Snow to see if there was any chance anyone at Minitex might know where it came from, and she sent me the original symposium presentation before I could turn around. That’s Minitex for you!

Here’s the bit that struck me so strongly: though a lot of good things had happened, Alice Wilcox saw trouble ahead:

We lost the opportunity to maintain a healthy balance between the private and the public sector. Instead of appreciating the roles and contributions of each, we blurred the distinctions. We failed to understand the difference between being business-like and being a business. In addition to sitting on the sidelines as observers, we have often participated in the diminution of the not-for-profit sector.

She said this in 1984. What a Cassandra. Reading this years later, I got chills down my spine.

I want to draw from her reflections to think about where we’ve been and where we might go, because she laid out our options so clearly.

First, the background. Fifty years ago, Alice Wilcox saw that librarians were beginning to face two opposing forces: more information was becoming available than ever before, and fewer funds were going to libraries to collect that information. There needed to be a new understanding among libraries that sharing would make us all stronger. That meant developing both bibliographic utilities so we’d know who had what, and systems for physically delivering materials – because materials were in print back then. Both of these needs depended on forging new human and institutional relationships informed by a vision for what libraries are all about. I’m going to quote Alice Wilcox again.

Independent of any grand plan, and within less than a decade, the continental US was covered with regional and state library networks. Thousands of formerly independent libraries voluntarily chose interdependent relationships and joined a network. Startling decisions were made regarding bibliographic and physical access to their collections. The magnitude of this rapid change was an amazing phenomenon.

She saw this not so much as a top-down decision, but a groundswell, one that fit in with Minnesota’s traditions of civic participation, grassroots cooperation, and a commitment to education – and with the backing of the University of Minnesota’s commitment to service for the public good. This, however, sometimes collided with personal agendas, institutional power dynamics, and impatience to move forward whatever the cost.

She identified a cluster of keywords, all beginning with the letter C – which she called the “confusing Cs.”

They included these positive ones: Collaborate, Cooperate, Community, Concern, and Create;

They included these positive ones: Collaborate, Cooperate, Community, Concern, and Create;

and these not-so-positive countervailing forces: Compete and Control. And I would add two more – Commodify and

Consume.

One the one side, we see tracings of the grassroots impulse to work together at all levels for the common good. On the other, the impulse to flex power and draw inspiration from capitalism and consumerism. It’s not for nothing that the early years of Minitex’s history occurred during a huge cultural shift, from the convention-challenging early seventies to the rise of a new neoliberal order, one in which the government was the problem, not the solution according to Ronald Reagan and, in Maggie Thatcher’s telling phrase, “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.”

If there’s no society, there’s no need for social welfare or social justice. During this period many public resources were dismantled or privatized; what remained of government was redeployed to support corporate interests, like funding the military-industrial complex and the carceral state, the tax breaks for big oil and deregulation for banks and other sectors of the economy. Forget about experts, the market in its wisdom will decide what’s best for us. Forget about commons and coops, it’s all about individual rights and free markets.

If there’s no society, there’s no need for social welfare or social justice. During this period many public resources were dismantled or privatized; what remained of government was redeployed to support corporate interests, like funding the military-industrial complex and the carceral state, the tax breaks for big oil and deregulation for banks and other sectors of the economy. Forget about experts, the market in its wisdom will decide what’s best for us. Forget about commons and coops, it’s all about individual rights and free markets.

This had a huge influence on education and libraries. In 1983, A Nation at Risk was published, depicting a crisis in which we were threatened by a “rising tide of mediocrity” that would put us at a strategic disadvantage with the rising Asian power that threatened our position in the world – that was Japan at the time. It was framed in pretty hysterical terms, like “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war.” There were 18 members on the commission that produced this report. Only one was a teacher. Yet its dire tone had influence – it launched the regime of educational testing as a mark of school success and, though it didn’t recommend privatizing public education, its call for reform was used as an argument for “back to basics,” school vouchers, and charter schools.

In libraries, we saw a growing sense that we were in a competition, that we had to turn to the business world to learn how to market our services, grow our customer base, and provide excellent customer service – somehow under the impression that businesses automatically treated people better than we did. This gave rise to a whole host of management fads. What we needed to pull our socks up was Total Quality Management, or TQM. We were inspired by people who threw fish. We wondered who moved our cheese. There was even some experimentation with charging patrons for deluxe services – giving faster access to new bestsellers for a fee. The ALA came out against that firmly in 1992 with its Statement on Economic Barriers to Information Access. (Interestingly in 2019 library fines were added as a barrier, and we see many libraries taking note.)

In some respects, the turn toward management theories for inspiration was a throwback to early modern librarianship, when leaders like Melville Dewey and John Cotton Dana promoted scientific management principles. The American Library Association’s first motto was the uninspiring but highly businesslike line, “the best reading for the largest number at the least cost,” adopted in 1892. I was surprised to discover it was reinstated by the ALA in 1988. Perhaps this is no coincidence.

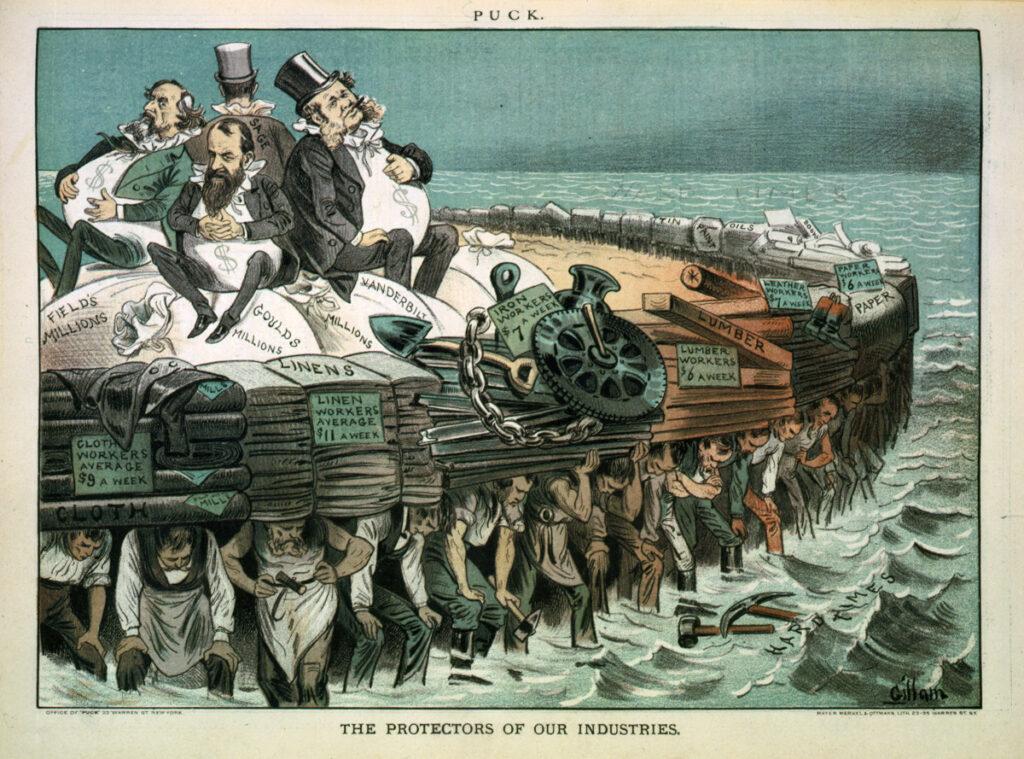

After all, ideas about being businesslike were dominant during the first Gilded Age,when corporations grew in size and power, when wealth was concentrated at the top while workers chafed under working conditions that treated them like interchangeable pieces of technology. This all sounds terribly familiar. It’s not a stretch to say the 1980s saw the emergence of a second Gilded Age, and the road to it was paved during Minitex’s first fifty years.

After all, ideas about being businesslike were dominant during the first Gilded Age,when corporations grew in size and power, when wealth was concentrated at the top while workers chafed under working conditions that treated them like interchangeable pieces of technology. This all sounds terribly familiar. It’s not a stretch to say the 1980s saw the emergence of a second Gilded Age, and the road to it was paved during Minitex’s first fifty years.

Some of you may remember the provocative cover story that American Libraries ran in 1998: “What if you ran your library like a bookstore.” It suggested libraries had lots to learn from Barnes and Nobles. What did the author think should we learn? Pay library workers minimum wage. Don’t bother with masters degrees or reference services, they cost too much. Centralize acquisitions and collection development. The author, Steve Coffman, had just founded LSSI, a for-profit company local governments use to outsource the management of their public libraries. In the past quarter century it hasn’t made a tremendous amount of headway in privatization, which pleases me no end. But I clearly remember how worried libraries were about obsolescence as B&N stores spread like Kudzu, using their size to crowd out local bookstores.

Academic libraries weren’t spared anxieties about competition. Students went to Barnes and Nobles to do their homework, oh no! Libraries were suddenly deserted, except – well, many actually weren’t. Certainly some good things came from this profession-wide panic attack. If it meant people could drink coffee in a library without hassle, I’m all for it. If it meant more book displays and public programming, great. But I always felt we greatly exaggerated the imminent death of libraries and underestimated the deep attachment people actually have to them.

A decade later, Google was the great threat.

Oh no, people can get information without coming to the library! So we added discovery layers, trying to emulate the seeming simplicity and ease of a Google search. But . . . it doesn’t quite work.

Google aims to do two things: appear to offer you millions of choices while also quickly pointing you toward the answer to your question. This became clearer in 2012 when Google began to show knowledge panels, preparation for voice assistants, like Alexa or Google Home who would read the answer to a search aloud in a helpful woman’s voice. By offering a search platform that, like Google, appear to provide answers quickly and efficiently, we obscure how research actually works. The illusion of fast, efficient choice flattens the complexity of how information is produced and shared and shaped by conversations across disciplines and across time.

This points to the problem Alice Wilcox gestured toward in 1984 – more and more information is being produced, and we’re all struggling to keep up with it. There was an interesting paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this month that pointed out an unintended consequence of measuring scientific progress by counting publications: New ideas get lost in the deluge and the same papers get cited more and more. This abundance comes as scholars and scientists feel the pressure to publish as a measure of their worth.

Peter Higgs, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who postulated the existence of the Higgs Boson, told a reporter he wouldn’t survive in academia now because he didn’t churn out enough papers. He needed time to think. How many good ideas are getting lost in the shuffle? How many never happen because of the pressures to seem productive?

Public librarians may experience something similar. Despite predictions that an abundance of new titles would enable a “long tail” in trade publishing, that everyone would be able to discover the books that satisfied their niche interests, the millions of new titles appearing every year – many of them self-published – makes it hard to choose, so publishers are more likely to turn to known quantities, familiar authors and sure bets.

And, of course, we see the frantic competition for attention on social media, which often brings out the worst in us. The algorithms want engagement, and engagement grows out of emotions – especially fear and anger, us versus them. Libraries feel compelled to be present on social media and often add social media “share” pixels to their websites despite the fact that they feed personal information to Facebook and other platforms without patron consent. In higher ed, we’re told we have to quantify our value by gathering data on our students. Supposedly it’s for their own good, but trying to correlate good grades with library visits in the name of “student success” ignores the complexity of students’ lives and is used to justify library budgets. If we can prove our value by spying on our students and generating lots of numbers, maybe we’ll be allowed to exist. We sacrifice our values to demonstrate our value in economic terms.

So, is this an inevitable trajectory? Where will we go from here? What will the next fifty years look like?

Will we see more concentration of economic power and wealth? More monopolies and mergers? An acceleration in the frantic production of stuff and more metrics generated to prove our worth, even at the expense of privacy or attention paid to things that defy measurement? Will we try to do more and more with less and less, even in the face of climate catastrophe and economic injustice? Will we see more focus on control, competition, commodification, and consumerism?

Or will we focus on those things that made Minitex what it is in the first place? Will we focus on cooperation and collaboration? Will our idea of community extend beyond our library? What will we create out of our concern for the public good?

I hope we will promote equitable open access to knowledge and the tools for making knowledge and art for all. I hope we will demonstrate concern for the common good by fighting for fair economic policies and doing what we can to support a healthy planet. I hope we will provide support for equitable and just communities. I hope we will show that collaboration and cooperation are a healthy alternative to austerity, competition, and a winner-takes-all mentality.

Let’s prove that library values – a set of operating principles we’ve developed over the decades since we first said libraries should be free for all – can be a valuable alternative to what Jillian York has termed “Silicon Values:” an emphasis on growth, global domination, engagement at any cost, and (of course) profit, all shaped by ignorance about anyone who isn’t white, male, and wealthy. Silicon values include a casual indifference to privacy, a simplistic understanding of free speech, and a near-total lack of accountability to the public.

Our values, in contrast, are a pretty radical challenge to the status quo. For a refresher, here are the core values spelled out by the American Library Association:

- Equal access to information for all

- Support for lifelong learning, so education doesn’t stop when we leave a classroom

- Democracy, which includes a democracy of intellectual pursuits and cultural tastes, as well as responsiveness to our community’s needs.

- Privacy as a condition necessary for free inquiry

- Intellectual freedom, including resisting attempts to rewrite history or to silence the voices of LGBTQ, black, indigenous, and people of color while also understanding that some kinds of speech itself can be silencing, a tricky balancing act that Silicon Valley hasn’t mastered.

- Preservation of our records of culture

- Sustainability so that we can act in ways that minimize harm to the planet while promoting community understanding of what’s at stake and what we all can do. (I was pleased to see this value added a couple of years ago.)

- Service, social responsibility, and a dedication to the public good over private interests

That’s quite a list! And it shows why we need Minitex. Yes, we are all local, serving specific communities with different needs, but no one library can do all this. A small public library has to weed its books to make room so they can give their patrons a current collection. We can’t expect that library to preserve everything. Nor can a community college library afford to provide its patrons with access to everything – nobody could afford that, not even the largest research library. To meet the challenge of sustainability we’ll have to get together to figure out how to re-imagine our work in a more ecologically responsible way. We can individually commit to the public good, to democracy, to lifelong learning, but we need all of us to fulfill the role libraries have in our society.

If we reject the idea that self-interest is the primary driver of human behavior and that moneyed interests should make decisions for us – if we reject Compete, Control, Commodify, and Consume, if we refuse to sit on the sidelines and instead fight to restore “a healthy balance between the private and the public sector” – we can work together to support individual expression, personal growth, healthy communities, social justice, and the greater good. We can remember the early lessons of Minitex and take heart in the fact that we still have libraries in spite of everything as proof that we already have an ethical blueprint for building a social infrastructure that is more just, equitable, and sustainable. I feel confident that Minitex will build on its past half century to help us do this work during the next fifty years.

(Photos of Minitex history courtesy of the Minnesota Digital Library and the MULS timeline.)