Reposted from Inside Higher Ed. Photo courtesy of Geoffrey Fairchild

I suppose it’s inevitable, given that information-driven tech-centered global corporations dominate the list of Big Rich Companies, that information systems play a significant role in 21st century terrorism. ISIS has famously made effective use of social media platforms for recruitment purposes. So have white nationalists and neo-Nazis. The responses have been fumbling, partly because the job of moderating messages that globally flow by the billions is difficult and partly because that flow is the current that produces power and money for these companies. Our devices and platforms want to seize and retain our attention and categorize our passions; building in methods to check the flow adds cost and conflicts with their very design. So that’s one thing: our most powerful information channels today are unprecedented in their usefulness for creating global connections among people who seek people who feel the same anger – and in their design-driven capacity for fanning those flames.

Then there’s the news media, which has always been prone to hyping stories about violence because they get our attention. “If it bleeds, it leads” is an old saying, but now the news media are dependent on advertising intermediaries who have captured most of the attention market and the ad dollars that media rely on. In reality, nearly all of the violence in our country goes uncovered, because it’s Tuesday; what’s new? But a terrorist act committed here or abroad will get non-stop coverage even when the only “news” available is a few cell phone clips played over and over with vacuous commentary. This propensity to play up danger does nothing to help us understand why these things happen, but it promises disaffected and angry young men the chance to be on television, action heroes displaying the rage they feel, people who suddenly are seen as belonging to something big. It’s trite to say “that’s how the terrorists win,” but . . . that’s how the terrorists win.

Third, there are governments that use these events to bolster their power. It’s not safe when states hoard vulnerabilities so they can exploit them. It’s not safe to break encryption. The trouble with creating back doors for the government is that other people will use them, and we are so incredibly dependent on encryption for basic things, not just texting each other or shopping online. We need encryption for securing global financial transactions, keeping medical records, running the electrical grid, and on and on. Demands to give the keys to governments in the name of security endanger our security.

Collecting it all has brought other problems. In the UK, as in the US, money has been poured into building a massive surveillance state. New laws continually expanded the power of the state to monitor British citizens (though the courts are pushing back). Yet in the two most recent attacks, collecting it all didn’t help. It probably hurt. Citizens tried to report suspicions they had about the perpetrators, but couldn’t get anyone’s attention. When everyone’s a potential target, it’s hard to find the needle in the haystack, and building bigger haystacks with artificial intelligence-driven needle detectors isn’t working. Following up on tips is everyday policing, but budget cuts to social programs include reductions in the number of police who can respond to their communities.

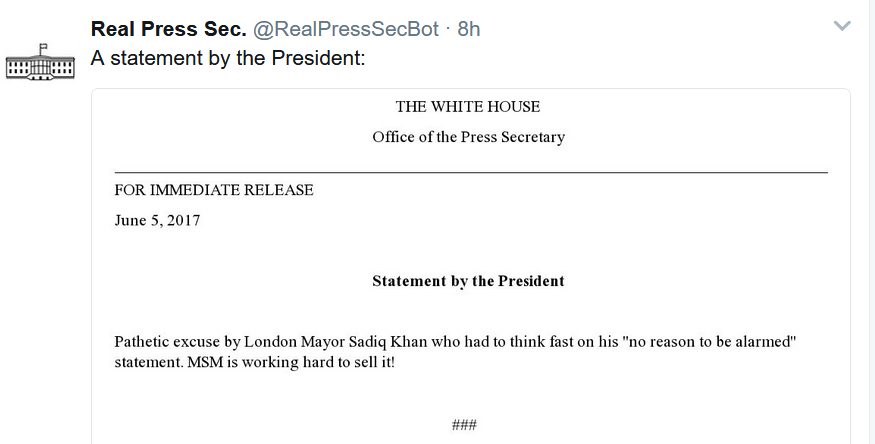

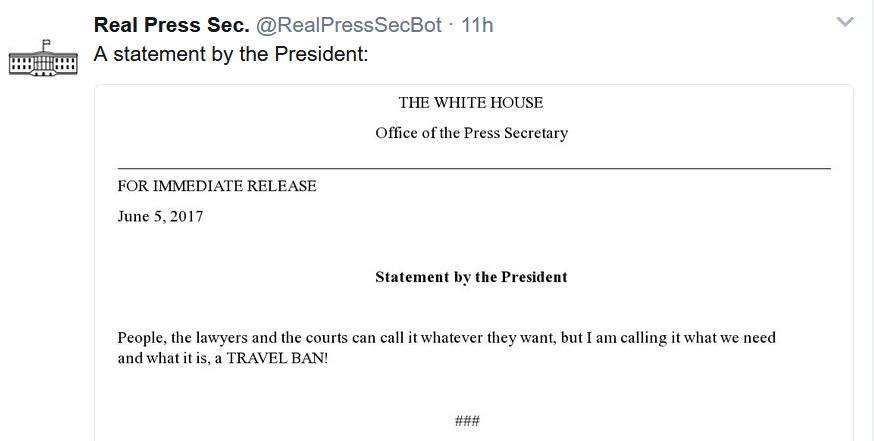

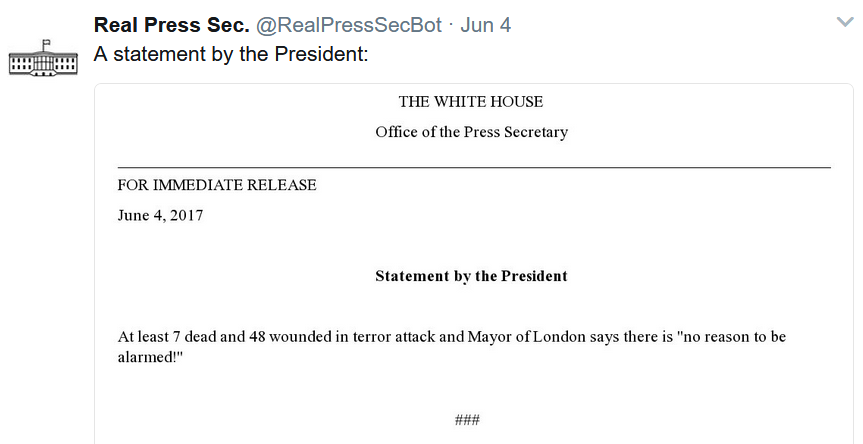

And while we’re talking about information systems, there’s also the new ways we get statements from the White House.

Russel Neiss created a clever bot to put the president’s statements in the form of presidential statements. It may look amusing, but it’s not a joke. The president is the president, and what he says in public is an official statement, not some private citizen’s late-night Tweets. It can be frustrating to see press time given to trivial and silly remarks, but it’s even more frustrating to see our president engage in trolling as his primary public form of foreign and domestic policy. I’m not sure it’s fair to blame this bizarre situation on social media, but clearly the combination of widespread anger, increasingly polarized news consumption, and the attention-addiction design of powerful social media platforms (quite apart from the detailed digital profiles being used to get people to the polls and the digital mischief being used to confuse us on our way there) has made it difficult to discourage the president from insulting our allies and . . . well, making statements that help the terrorists win.

So what to do? Hold Facebook, Google, Twitter et al accountable. Stop feeding the dreams of terrorists by making them stars in television action dramas. Hide the president’s phone? I admit, there aren’t easy answers, but what a toxic information brew we’ve created. We’re going to have to figure this out, and soon.